Doc Corner: Keith Maitland's 'Dear Mr. Brody'

Friday, March 4, 2022 at 9:26AM

Friday, March 4, 2022 at 9:26AM By Glenn Dunks

Sometimes it is those brief moments in history that can offer the greatest glimpse at the changing state of a nation. Keith Maitland does just that with the story of Michael Brody Jr., a blip on the radar of pop culture by today’s standards, but who in 1970 at the age of 21—a self-proclaimed hippie millionaire, the heir to a large margarine fortune—caused pandemonium when he declared his intentions to give away his entire wealth to anybody who asked for it...

Maitland’s previous film was Tower, an excellent blend of animation and archival footage (several years before current Oscar success Flee) and which achieved a similar accomplishment on the subject of mass shooting. Brody’s 15 minutes of fame ended with his death at the age of 24, but the legacy of his actions as shown in Dear Mr. Brody give a more accurate representation of the United States than any political ‘state of the nation’ could attempt.

Looking at it now, Brody’s nation-wide notice of intent to part with his inheritance was always somewhat skeptical. Not least of all because the amount of his bank account wavered frequently between $25 million to $500 million to, well, limitless. But like the lottery, many saw no harm in trying. Wishing and hoping that finally somebody from money was actually not concerned with just the betterment of their own wealth, they wrote him letters from every corner of the country detailing why they would like of that immense fortune.

For some it was a matter of life and death—medical bills, poverty and domestic violence. For others it was practical—starting a new business (beauty salons were popular, a double-tiered cereal bowl was another) or school fees. But for all it was an overriding thought that money will change their lives. They wouldn’t be wrong. We can bemoan society’s obsession with money and wealth all we like, but it’s not hard to see why Brody was bombarded with attention. His residences were stalked, his telephone rang off the hook, and despite pleas to the public to leave him alone and to let him read all the letters, he was harassed night and day. It’s a little bit Willy Wonka and a little bit Brewster’s Millions.

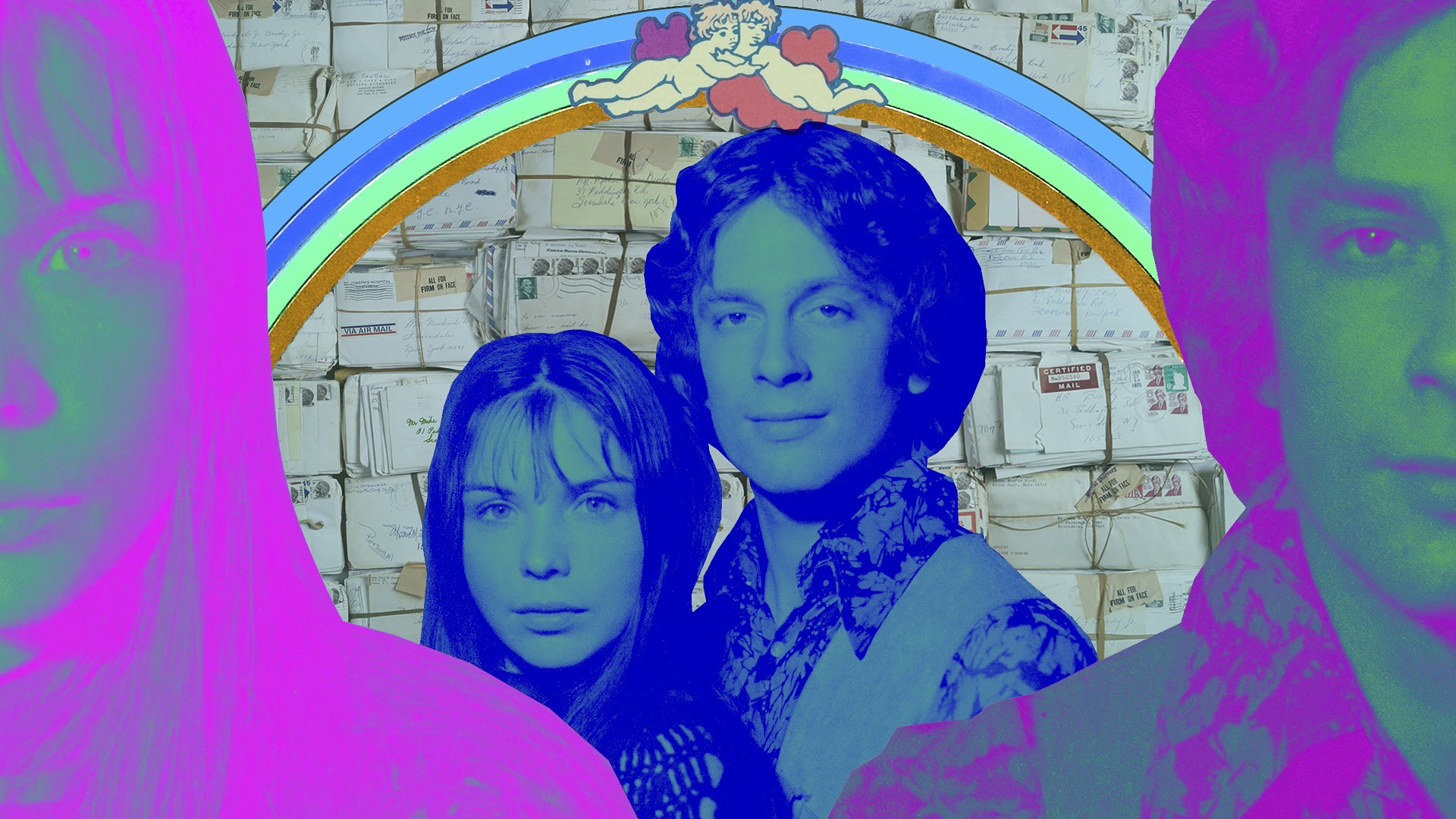

Maitland has invested his film in a wonderful sense of visual design. Dear Mr. Brody is a riot of colourful animations, archival footage, stock material, newspaper clippings, photograph patchworks, narrations, film clips, trippy collage, dramatic readings, and mobile phone video. A series of gleeful directorial choices that not only amplify the material but excite the eye and lend this wild moment in American history with a bold sense of style. It is once Brody’s real story is revealed and the visual flash subsides somewhat (even then, it’s never a boring film to look at), it’s more prominent themes emerge. Brody himself subsides to the narrative background and in his place are those who wrote the letters and/or their family.

Our on-screen guide is Melissa Robyn Glassman, an archivist for film producer Ed Pressman. He was preparing a film about Brody in the 1970s to star Richard Dreyfuss (at the time, he’d produced Terrence Malick’s Badlands and Brian De Palma’s Sisters and Phantom of the Paradise) and gained possession of boxes and boxes of the mostly hand-written letters asking for financial assistance. More letters come later from the home of Brody’s son, an infant when his father died. Glassman and Maitland track some of these people down, discovering untold stories of pain, suffering and inequality. In some cases they read the letters aloud. In others, actors in period settings and costumes recite them as if they would have when putting pen to paper. In one remarkable case, they find two separate letters from two separate people from the same home telling the same story of abuse, previously unaware that such a cross-over had happened.

So many of those who wrote to Mr Brody (so far 31,334 unopened letters have been found) suffer from all manner of inequalities that emphasises the persistent issues that have plagued the United States since its inception. It proves that the so-called greatness that many are eager to go back to was always a fallacy. I maybe wish Maitland hadn’t laid out this point quite so explicitly in its final moments; it figures to me that audiences would be smart enough to have figured it out themselves. But it’s a modest frustration in an otherwise strong film.

The events of Dear Mr. Brody remain shocking; an individual fleeting moment of temporary insanity in a culture built from them. I, personally, had never heard of the Brodys. I suspect that will be the case for many. Even for those who were alive at the time as when Michael Brody Jr.’s story crested in the public eye (he even appeared on the Ed Sullivan show) have likely forgotten about the particulars just as we today will surely forget all about whatever ridiculous scandal takes over the press cycle for a week. But the events of Maitland’s film aren’t just a laff. It’s not just a chance for an audience to chuckle at the naiveté of these people. It’s a reflection of something bigger than itself.

Release: In limited theatres as well as streaming from today.

Awards chances: I'd like to think so, but a March release will always struggle if its profile isn't big enough by the end of the year. Hopefully it builds momentum on streaming.

Dear Mr Brody,

Dear Mr Brody,  Doc Corner,

Doc Corner,  Keith Maitland,

Keith Maitland,  Reviews,

Reviews,  documentaries

documentaries