Hou Hsiao-Hsien @ 75: Independent Auteur (1983-1986)

Saturday, April 9, 2022 at 9:00PM

Saturday, April 9, 2022 at 9:00PM

After abandoning studio moviemaking, Hou Hsiao-Hsien became more evident in his cinematic references. Some of his post-1982 films even featured excerpts from De Sica's Bicycle Thieves and Visconti's Rocco and His Brothers. Fellini's I Vitelloni was never as obviously showcased, but 1983's The Boys from Fengkuei owes much to that Italian classic. The film portrays the aimless wanderings of bored teenagers from a small shipping island. Before the boys are called for their obligatory military service, they travel to the big city of Kaohsiung, finding new independence, new loves, and new woes.

Instead of forcing an artificial structure unto his character's existence, Hou Hsiao-Hsien follows their insouciance with patience, making the film in their likeness...

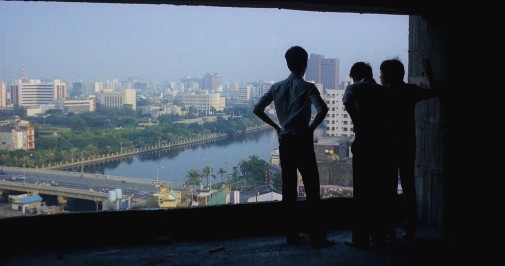

THE BOYS FROM FENGKUEI (1983)

THE BOYS FROM FENGKUEI (1983)

Moreover, there's great frankness in how their dilemmas are portrayed, often serving as a synecdoche for an entire nation's identity crisis. For example, during a pivotal scene, the youths are conned into paying to enter a movie house that, in reality, is nothing but a construction site. Gazing through the hole of a windowless window, the Boys from Fengkuei regard the distant cityscape as a movie. The languid reality of modern Taiwan transforms into cinema through the mere presence of a frame.

To understand how this work came to be, one must acknowledge the context in which it was made. Emboldened by the Taiwan New Cinema movement whose circles he frequented, Hou Hsiao-Hsien started to distance himself from the commercial studio scene, independently making most of his post-Green Grass of Home films. Also in 1983, he directed the titular chapter of The Sandwich Man, an anthological movie often regarded as one of the pioneering moments in this cinematic vanguard.

A SUMMER AT GRANDPA'S (1984)

A SUMMER AT GRANDPA'S (1984)

What followed was to be the first unofficial trilogy to take Hou Hsiao-Hsien's cinema to another level of artistic ambition, accomplishment, and acclaim. From 1984 to 1986, beyond co-writing screenplays for the likes of Edward Yang and Kun-Hou Chen, Hou Hsiao-Hsien directed films directly inspired by childhood memories, including his own. The first of these pictures is what I consider to be the director's first outright masterpiece – A Summer at Grandpa's.

Based on the youth of screenwriter T'ien-wen Chu, the film follows a brother and sister as they go spend the summer at their grandparent's countryside home. While the film is a study of childlike innocence, darkness looms on the periphery of the two protagonists. The reason for their bucolic idyll is their mother's sickness, and there's no shortage of adult violence happening around them.

From the grandpa's disappointment at the kids' feckless uncle to a moment of witnessed bloodshed, death looms over this memorable summer, shaping the film into a study on how children grow up by observing and mulling over the mysteries of adult lives. 1985's A Time to Live, A Time to Die upped the autobiographical intent of A Summer at Grandpa's, detailing Hou Hsiao-Hsien's adolescence in stark detail and going so far as to be set in the director's real family home.

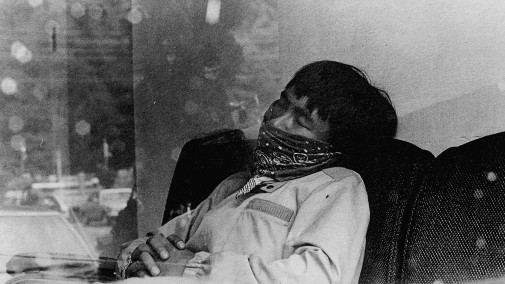

A TIME TO LIVE, A TIME TO DIE (1985)

A TIME TO LIVE, A TIME TO DIE (1985)

At times, the naked honesty is brutal to endure, though the film is never less than gorgeous. Working, for the first time, alongside cinematographer Ping Bin Lee, Hou Hsiao-Hsien perfected the aesthetic that would characterize the majority of his work. Rich in shadow and natural light, the film is a staggering collection of images, each more powerful than the one which came before.

The humble shot of an old woman's hand scaled by a gentle stream of ants is heartbreaking beyond words. Much of Hou Hsiao-Hsien's cinema defies description, it must be said, for these films depend on the audience's immersion, their gentle lulling into a state of transcendent visual poetry. The memoirist trilogy came to an end with Dust in the Wind, based on the life of screenwriter Wu Nien-Jen.

DUST IN THE WIND (1986)

DUST IN THE WIND (1986)

For the first time, the shadow of obligatory military service materializes in Hou Hsiao-Hsien's cinema, bringing new milieus into a tale that, like all his previous films, hinges its conflict on the tensions between the country and city, the old and the modern, Mainland China and Taiwan. Some new strategies also make their debut here, like a taste for dreamed memory intruding upon the characters' mundane lives and a more regimented, almost musical, attention to rhythmic movements.

Most filmmakers could have settled for such accomplishments without pushing themselves toward new heights. However, Hou Hsiao-Hsien isn't most filmmakers. The end of the 80s would see him try to regain some commercial appeal before giving up on such follies. More importantly, the decade's twilight marked the end of martial law in Taiwan, allowing the director to explore the country's thorny history with more focus than before. More on that tomorrow.

10|25|50|75|100,

10|25|50|75|100,  Asian cinema,

Asian cinema,  Hou Hsiao-Hsien,

Hou Hsiao-Hsien,  Taiwan

Taiwan

Reader Comments (3)

OK, this will help me to get to understand Hsiao-Hsien though I do own a few films by Edward Yang.

Excellent post (as usual), and I just want to chime in to say that features like this are why this is the best “awards blog” out there (in quotes because that’s clearly not all you cover). While other blogs in your category are still devoting most of their coverage to The Slap, here we get a full series on Hou Hsiao-hsien, one of the best filmmakers in the world regardless of the fact that he’s never been remotely relevant to the Oscars (which I think is perfectly fine; he’s in the category of filmmaker-poets who are frankly above all that, if that’s not too snotty to say). Like one of his biggest influences Ozu, he’s a filmmaker whose every film seems to complement and enrich the others. Every time I see another of his films, I feel like my appreciation of the ones I’ve already seen deepens. While he’s definitely highly regarded among a relatively small group of cinephiles, I have a feeling that his stature will continue to grow over time as more people in the West are exposed to his films (I’m counting on Criterion to contribute to that by releasing more of his films following last year’s release of Flowers of Shanghai). He certainly deserves more attention, so thank you for doing this series.

thevoid99 -- Thank you for reading this series, even if you're not that familiar with Hou's work. I hope you give him a chance :)

Edwin -- Your comment brought me a lot of joy, thank you. I hope Criterion gets working on restoring some of his other movies since their FLOWERS OF SHANGHAI release is spectacularly beautiful. THE PUPPETMASTER, in particular, needs to be restored and made more widely available. I'll also shout out the Masters of Cinema series by Eureka. I have their early Hou Hsiao-Hsien box set plus the DAUGHTER OF THE NILE, and they're wonderfully remastered.