Queering the Oscars: "Common Threads: Stories From the Quilt" for Best Documentary Feature

Monday, July 3, 2023 at 2:00PM

Monday, July 3, 2023 at 2:00PM Team Experience has been looking at LGBTQ+ related Oscar nominations.

by Nick Taylor

Over the course of June, one of my big cinematic missions was to watch as many queer documentaries as I could. A broader understanding and recognition of lived queer experiences, either through art or lived interaction, is something I’m finding increasingly valuable and incredibly grateful for. Past or present lives, always reflecting so many potential futures - cherish that shit! Cinema allows for a unique view on long-gone lives I would never have met. A lot of my dive has been focused on the Criterion Channel’s various LGBTQ+ playlists. If you haven’t already seen Dressed in Blue, Tongues Untied, and Shakedown, watch them all now and learn from their authors, the multitude of voices in front of and behind the camera bravely willing to show us who they are and what they know.

Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt, was also a recent discovery, equally inspired by this series and by its renewed spotlight on Criterion. To those who want to see it but don’t have this particular streaming service, it is also free on YouTube). The film is one of two Oscar-winning documentaries directed by Rob Epstein in Criterion’s playlist, each representing worlds of grassroots activism on behalf of a queer America grappling with very different realities from each other. The Times of Harvey Milk is as committed to being a joyous celebration of solidarity and advancement as well as a hollowing eulogy for everything violently, permissibly stolen from queer America as Common Threads is, with its own fierce editing and poignant, unabashed political agenda...

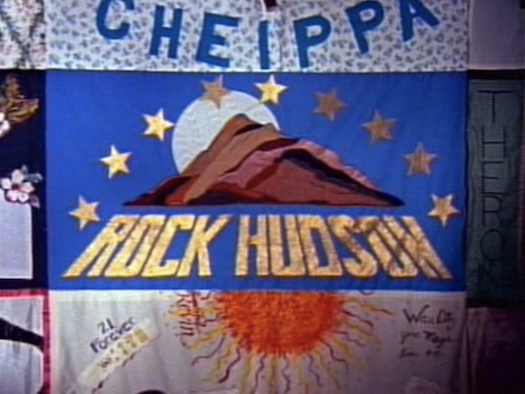

Common Threads focuses on five stories represented in the original NAMES Project Memorial AIDS Quilt. The quilt was conceived by Cleve Jones in San Francisco as a tribute to the thousands of men, women, and children who had died of AIDS and AIDS-related complications. Each panel of the quilt was hand-crafted as a tribute by the loved one(s) left to fill the void. Variations are allowed in fabric and decoration, but all panels measure at 3 x 6 feet, or the size of an average grave. Some names appear on multiple panels. Some panels hold more than one name, paying tribute to lovers and families that were wiped out all at once. Because AIDS victims were almost always denied a proper burial, the act of crafting, sewing, and displaying the quilt was the closest thing to a memorial service so many of these people ever got.

The quilt made its debut on October 11, 1987 on the National Mall in Washington D.C., as part of the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman were at the National Mall when the quilt was first shown, and decided then and there to make a documentary about the people whose stories comprised its fabric. They initially started with a pool of over 200 potential subjects, which they winnowed down to 50 or 60 people before deciding on the five deceased and six witnesses who would be the subject of their film. They are, in alphabetical order by last name:

- David C. Campbell, a landscape architect in Washington D.C., whose story is told by his lover, former US Navy Commander Tracy Torrey. The two met after Torrey had left his wife, and they initially bonded over a mutual attraction and their own mixed feelings about their homosexuality. David’s illness came very suddenly and took him very suddenly. Tracy testifies to their life together while lying sick from AIDS in his own bed - by the time we meet him he can barely lift his head, and his face is covered in lesions.

- David Mandell Jr., a 12-year-old hemophiliac whose story is told by his parents, David and Suzi Mandell. David and his parents committed very early in his life to trying to give him a “normal” life while accepting the medical risks hemophilia would inflict on a precocious, sports-inclined boy. They continued this even when it was revealed blood product could be contaminated with HIV - although continuing to perform these transfusions would expose him to a new danger, David and his family decided to accept that risk rather than the risks that would come from not giving him any blood product.

- Robert Perryman, whose story is told by his wife, Sallie Perryman. They are the only black interview subjects in Common Threads. Robert and Sallie met through their church, and did not know each other for very long before getting married. Robert struggled with drug addiction for years, with Sallie standing by his side unfailing through good times and bad. He was only able to stay clean after their daughter was born, five years into their marriage, and remained sober until he died. Robert contracted AIDS through intravenous drug usage.

- Jeffrey Sevcik, whose story is told by his lover Vito Russo, the film critic/historian famous for writing The Celluloid Closet. The two first bonded over shared tastes in pop culture, though Jeff being slightly younger and far more gentle and fragile and Vito gave them very different outlooks on how they handled their respective AIDS diagnoses.

- Dr. Tom Waddell, the founder of the Gay Games, whose story is told by his friend Sara Lewinstein. Sara, a lesbian herself, met Tom when she was a board member for the Gay Games, and the two became fast friends due to their competitive natures. Sara eventually asked Tom if he wanted to father a child with her, and the two had a daughter.

These summaries function as solid introductions for the five families we meet, to noteworthy events punctuating their lives even beyond the AIDS diagnoses, though I’m the first to admit these don’t provide any adequate scope of the texture and depth of who these people are. That only comes out in the interviews, in the montage of personal and national archives intermixed with the testimonies given by their surviving loved ones. “Surviving” in this case is a limited terminology, since three of the individuals giving these interviews have AIDS themselves. One will be memorialized at the end of Common Threads along with their partner, while another will die roughly a year after the film is released.

I hate if this ambiguity on who lives and who dies reads as something like spoiler-aversion or purposeful, suspenseful withholding, because I don’t want to frame this sort of human experience as a cheap narrative reveal. If that’s how it comes across, I apologize. That being said, what makes Common Threads so involving is the way it unspools the fates of its figures without making a treacly spectacle of them. No one is a paragon, and the storytellers describe their loved ones with their own degrees of admiration, sympathy, terrified bystanderdom, and even frustration at how some of them confront their fates. Children die without knowing their fathers, and parents die robbed of the person their son could've grown up to be. Death happens, and it is scary and personal and a goddamn national outrage. The film frequently punctuates jumps forward in time with new panels from the NAMES Quilt, underlined by new statistics of how many Americans have contracted and died of AIDS. Footage of gay activists speaking before Congress or leading marching ends with a newspaper headline or a quilt panel documenting a plea that they not die due to political inactivity, a plea that ultimately fell on maliciously deaf ears.

Common Threads is an angry movie, which is perhaps not the first word evoked by its soap-bubble sensitive score and the total humanity it allows to its subjects. But to so fully humanize this tragedy inevitably leads to anger that this mass-scale death was being tolerated. The sight of the quilt being assembled in workshops and studios, adorned with pictures and phrases and plushies and made with such tenderness it makes me want to cry, reminded me of Rithy Pahn’s The Missing Picture and Graves Without a Name, which examine a very different kind of cultural genocide through similarly unique methods of exorcising demons and using art and rituals to guide lost loved ones to the other side. The careful unwrapping and unveiling of the panels, bordered by large walkways of cloth for spectators to approach each panel, with every name read aloud by hundreds of participants at the National Mall, is both a rousing act of communal comfort and a heartbreaking sight of mourning.

I can feel my writing become floridly upset, which feels like it’s sitting on top of the simple humanity that comes from watching so many people participate in this event, in whatever way they can. There’s something genuinely gratifying to know that I can’t write about Common Threads any better than its narrators can eloquently, intimately describe their lives and the lives of the people they loved. Epstein and Friedman compose the film with gossamer delicacy that does not mask or undermine the potency of everything they ask us to witness, to listen to, to absorb and take with us and use in the creation of a better future that, at the moment of typing this, feels difficult for me as a queer American to imagine, approaching on the horizon, which makes it all the more urgent to fight for. Go watch this movie. Go be humbled, and moved, and take it with you however you can.

More 'Queering the Oscars'

- Actor - A Special Day

- Costume Design - Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert

- Costume Design - Orlando

- Documentary - Changing Our Minds

- International Feature - All About My Mother

- Original Song - Calamity Jane

- Screenplay - Heavenly Creatures

- Screenplay - The Damned

- Screenplay - Far From Heaven

- Supporting Actor - Dog Day Afternoon

- Supporting Actor - Longtime Companion

Reader Comments (4)

This film devastated me - such an empathetic portrait of a hideously dehumanising time in history. An incredibly deserving Oscar winner.

Beautiful write-up, Nick. I don't remember it being that angry. But I wouldn't be surprised given the directors.

@Andrew - I had a similar reaction when I first watched it. Such a galvanizing experience, and a much worthier winner than many of the category's recent winners.

@Glenn - I'm sure the anger is partially just my own reaction, but I don't think you can make a film this humanizing and this politically astute about a tragedy on this scale without inspiring anger in its audience. Thank you for the compliment - coming from someone who writes so eloquently about documentaries, that means a lot.

Stories From the Quilt" is a clear and poignant documentary that deserves recognition and acclaim.

Tecumseh Top Summer Camps & Care for Kids