TIFF '23: At the Crossroads of Old and New

Friday, September 15, 2023 at 7:00PM

Friday, September 15, 2023 at 7:00PM

During my days at the festival, I've found TIFF can be a place of great discovery, full of small titles coexisting with big ones, often besting them from a disadvantageous position. Discovery can also exist in the dialogues established between programmed projects, threads of shared ideas and ideals linking works of distinct artists from all over the globe.

Because of its status as Bhutan's Oscar submission and Pawo Choyning Dorji's follow-up to his nominated Lunana, I would always see The Monk and the Gun. However, the conversations it shares with other, less high profile films, were a welcome surprise. Despite their disparate genres (comedy, character study, tragedy) themes of encroaching modernity within traditional communities of mountainous Asian nations echoed back from the Nepalese A Road to a Village and the Mongolian City of Wind...

THE MONK AND THE GUN, Pawo Choyning Dorji

BHUTAN'S OSCAR SUBMISSION

The success of Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom put Pawo Choyning Dorji's name on the map. Indeed, one can be justified in saying it helped set the Bhutanese film industry on a higher pedestal than it had ever enjoyed. So, it's only logical that expectations were high when the director announced a subsequent feature, vying for the same seal of Academy-sanctioned approval that helped the story of a young teacher in Bhutan reach so many viewers worldwide. Great expectations can be a blessing, but they're just as often a curse, and it's with no pleasure that I say The Monk and the Gun falls victim to the latter fate.

This time, the narrative is pointedly broader, in tone and scope, looking back to 2006 when the Kingdom of Bhutan's beloved monarch abdicated to facilitate his country's rise as a democratic nation. One would suppose this news would cause great rejoicing, but it isn't so. The predominantly rural population the film presents is resistant to change and must be taught how to participate in the democratic process. The very concept of organized voting requires explanation, prompting authorities to set up mock elections as a trial run before the real thing. With the eyes of the world on Bhutan, everything must go according to plan, or it will be a national shame.

The remote village of Ura is selected for this experiment, prompting officials to drive into their country's pre-industrialized pastoral recesses, fretting through the entire ordeal of registering voters who don't even know their birthdays. At the same time, the looming pressure of political choice splits local families apart, men fighting with their mothers-in-law over the correct candidate to back up. There's also an American arms collector going around, intent on buying a Civil War-era rifle that somehow found its way into Ura. Oh, and the monk from the title is also there.

The monk is at the service of a respected lama who, upon hearing about the recent news, demands two guns for some mysterious purpose. Initially dispersed throughout the narrative canvas, these storylines overlap and converge, in near-screwball style until the day of the mock elections delivers an expectedly sweet conclusion. That'll be pleasant to some, and cloying to other viewers. Is Dorji's apolitical feel-good approach appropriate for such a story? At times, it can feel downright anti-democratic in its farcical rhetoric.

Still, that's not the picture's biggest sin. The foremost problem that precludes The Monk and the Gun from its predecessor's quality lies in catering to an outsider's perspective, all too eager for crowd-pleasing notices from overseas. As odd as it sounds, the framing logic often posits the American within the chaos as a point of identification, extending a hand to international markets to the detriment of a more authentic presentation true to its roots. Of these three titles, the comedy's clash of modernity and tradition is the most infantile, reducing entire figures and their conflicts to cartoons because that's how they're best used for laughs. If it were funnier or had any bite, these issues could be ignored. Sadly, that's not the case.

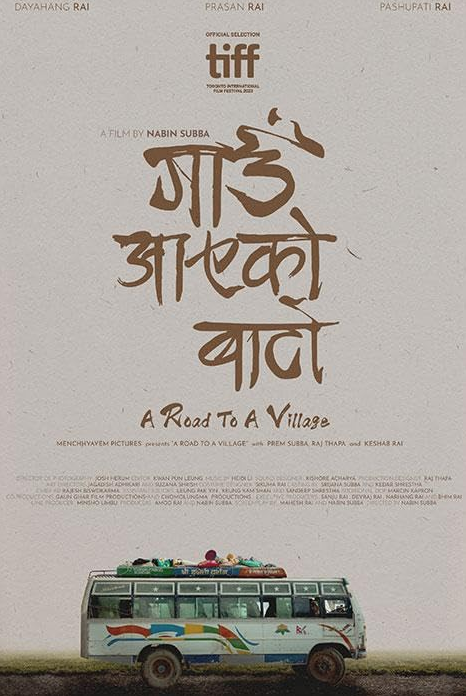

A ROAD TO A VILLAGE, Nabin Subba

Some films are a tonal flatline. Others are rollercoasters, frenetically up and down. A Road to a Village is closer to the latter than the former, wavering between registers, from the most charming comedy to the pits of sorrow. It all starts with the titular road, a new dirt construction carved into the mountainside near an isolated community in Nepal. Suddenly, the modern town nearby becomes accessible, and past meets present with a resounding boom. New amenities are available to those with funds to buy them, technology walks into where it had never been before, TV fun and Coca-Cola galore. But, along with the blessings, come the vices of "progress".

Then again, to label the effects on the village's way of life as the result of modernity might be missing the point. More accurately, it's the economic systems and capitalist materialism that do the damage. A TV or the newness of electricity wouldn't be such a Pandora's Box of temptation if their possession weren't so exorbitantly priced, elevating the commodity to a status symbol and forcing people to leave the community to find better-paying work elsewhere. Some would say that if you don't know what you can have, you won't feel its absence when it's not there; The gift of knowledge is the curse of yearning.

For Maila, a basket weaver, the effects are immediate, his labor made obsolete as plastic tarp substitutes woven bamboo. And yet, his little seven-year-old boy, Bindray, is so charmed by all the new things available to him that it's hard to hate the change. It's even harder to resist his pleading eyes. But change will always be difficult. Progress demands it, of course, along with growing pains of collateral damage. And so, Maila's family life changes at an alarming pace, careening out of control as the patriarch's craft is devalued and his avenues of revenue dry up. Anxiety surges while, at the same time, Bindray is living through a sweet little comedy of his own, wielding soda as a tool of authority in playground politics.

Subba is patient in acknowledging that, when the road came, something was gained and something else was irreparably lost. The director's humanist efforts detail the evolving awareness of consequence, the frog's realization that the water it's been resting in has been heating up to a boil. It's a tricky balance made more impressive by Subba's formal choices, opting for a predominance of wide shots and distancing devices that never corrupt the picture's sweet soul with stabs at alienation. While I question the need for A Road to a Village's ultimate swerve into tragedy, everything that precedes it is the work of an accomplished image-maker with a gentle but sure hand behind the camera. Facing the crossroads of old and new, this gem of a movie never falls to reductivism, maintaining a clear-eyed view of the good and the bad. It's melancholic even when it laughs, hopeful when wiping tears away.

CITY OF WIND, Lkhagvadulam Purev-Ochir

At one point in the Venice prize-winner City of Wind, Ze, a teenage boy doing part-time work as a shaman in modern day Mongolia, visits a nightclub. He's been doing it with increasing frequency ever since meeting a girl with whom he sparked an instant connection. Well, he did, while she mostly expressed skepticism toward his religious practices. Lost in the darkness of nightlife, a world away from the tent where he performs his rites, Ze's face shapeshifts in the strobe lights, from blue to red to black again. Each flash of color reveals a different visage carved in shadow, like magic masks clicking into place.

The camera remains on him, ignoring the revelry around, as if fascinated by the unresolved process, waiting to see which look will remain after the strobing ceases. To be stuck in a state of transition, distinct possibilities flashing by is both an arresting image and a startling illustration of what is to be on the cusp of adulthood. City of Wind is about many things, teen romance among them and, of course, the contrasts between a lifestyle founded on tradition within a modern world - spiritual possession by morning and scrolling through Instagram by lunchtime at school.

I won't go into much more detail because Elisa already reviewed City of Wind at the Mostra. At that festival, Tergel Bold-Erdene, who plays the youth at crossroads over crossroads, won the Horizon section's Best Actor prize. Though I have not seen the rest of the competition, arguing against the recognition is difficult. His Ze is a storm of internalized conflict thundering silently across the screen, trying to decide what he'll be in the mystery of his own future.

Maybe, after all, when juxtaposing these three films, one comes to realize that the encroachment of modernity on the old customs of Asian countries isn't the primary connection between them. Instead, it's a matter of decision, choice, change as universal concepts, the wonder that comes with them, and the struggle, too. What face will we be wearing when the strobing stops?