Unsung Heroes: The Editing of 'Glengarry Glen Ross'

Thursday, June 2, 2011 at 4:16PM

Thursday, June 2, 2011 at 4:16PM Michael C. from Serious Film here this week with an appreciation of the craftsman that took what could have been an incredibly un-cinematic project and turned it into one hundred of the most riveting minutes of the nineties.

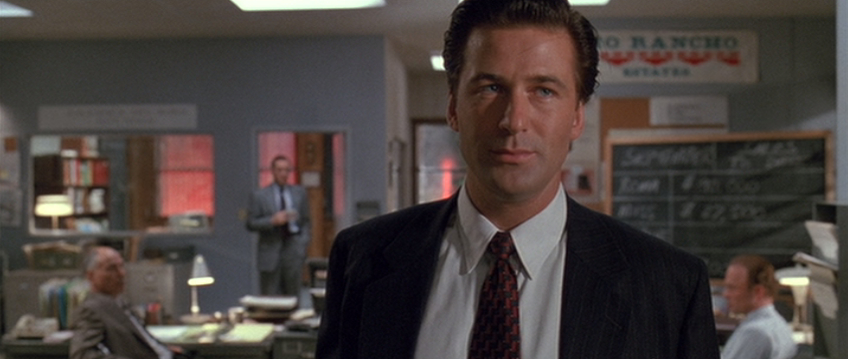

Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Whenever a prominent stage play makes the trip to the big screen it is, without fail, greeted by throngs of film writers questioning how well the material has been “opened up” for the big screen. This always gets under my skin. Never mind that many, if not the majority, of the most beloved stage adaptations were not “opened up” at all. No, what gets me is the implied idea that there is something inherently uncinematic about dialogue. As if audiences say things like, “I guess it’s okay when Sidney Poitier tells Rod Steiger they call him Mr. Tibbs, I just wish they were doing something cinematic at the time, like dangling from a helicopter.”

a desperate phone call with Jack LemmonThe truth, of course, is that any film that makes you identify with the events on screen is cinematic. It can take place entirely in a restaurant, a jury room, or the mind of one paralyzed man; if it makes you forget the darkened theater with the sticky floor it’s doing its job.

a desperate phone call with Jack LemmonThe truth, of course, is that any film that makes you identify with the events on screen is cinematic. It can take place entirely in a restaurant, a jury room, or the mind of one paralyzed man; if it makes you forget the darkened theater with the sticky floor it’s doing its job.

Director James Foley along with editor Howard E Smith knew this when he made the film of David Mamet’s Pulitzer Prize winning Glengarry Glen Ross (1992). To paraphrase what he says in the DVD commentary, Ed Harris smoking a cigarette is as much a movie moment as Lawrence of Arabia coming over a hill leading a thousand men. In the lesser Mamet films, the stylized writing can feel stilted and airless, but not this time. Throughout Glengarry we feel as if we are privy to the interior monologues of the characters.

I could fill ten columns highlighting perfectly constructed moments but I’ll limit myself to three favorites:

Al Pacino's nomination was the only Oscar attention for the film

Al Pacino's nomination was the only Oscar attention for the film

- Any discussion of Glengarry has to begin with Alec Baldwin’s legendary scene. It's an audacious move to begin the movie with one actor delivering an uninterrupted eight-minute monologue, but Foley and Smith get away with it largely by breaking the whole sequence down into a series of short scenes – Baldwin belittles Lemmon, Harris confronts Baldwin, Baldwin denies them the leads – that add up to one riveting whole.

- There is a perfectly held moment just after Spacey has opened his big mouth and blown Pacino’s big sale and just before Pacino lets loose with one of the most memorable torrents of profanity in film history. It just holds on Pacino’s face as he absorbs what has just transpired, giving the audience an all time great “Uh-oh…” moment watching the fury gather behind his eyes.

- I love the way the filmmakers relax the film’s tension just long enough to let Lemmon’s Shelly “The Machine” Levine recount what he believes to be his great triumph to Pacino. It’s a small oasis of peace and contentment before the character’s final slide down to destruction.

Throughout the film there is never a cut for it’s own sake, never a moment where Foley and Smith showoff just to prove that it’s a movie they’re making. Instead they rely on the basic language of cinema to give the bouts of verbal violence an impact that makes most movie violence feel like playing patty-cake.