The State of the State of Cinema

Thursday, May 2, 2013 at 7:33PM

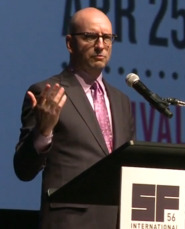

Thursday, May 2, 2013 at 7:33PM  Hey everybody, it’s Tim, here to add my two cents to what has been, incontestably, the film story of the last few days: the sprawling, self-described “rant” delivered by Steven Soderbergh as his keynote speech on the State of Cinema at the San Francisco Film Festival on April 27. The San Francisco Film Society has made the video of his entire speech available, accompanied by a not-quite-accurate transcript; it’s worth checking it out in either form, though I found it easier to puzzle out what the director was getting at in the text version.

Hey everybody, it’s Tim, here to add my two cents to what has been, incontestably, the film story of the last few days: the sprawling, self-described “rant” delivered by Steven Soderbergh as his keynote speech on the State of Cinema at the San Francisco Film Festival on April 27. The San Francisco Film Society has made the video of his entire speech available, accompanied by a not-quite-accurate transcript; it’s worth checking it out in either form, though I found it easier to puzzle out what the director was getting at in the text version.

By all means, it takes some puzzling. I yield to no-one in my love of Soderbergh, but there’s no denying that his speech is very much a rambling, discursive piece, meant to be enjoyed as conversation, rather than analyzed closely for a structure it very much does not possess. It’s pure stream-of-consciousness (it wouldn’t be the least bit surprising to find out that it was predominately improvised), and that’s okay: anybody who has listened to one of Soderbergh’s DVD commentaries is well aware that when he gets to rambling, some very keen insights on the nature of the art form tend to come tumbling out...

That being said, I’m not entirely certain that his State of Cinema address ends up being especially keen. The entire speech hinges on his proclamation, about a third of the way through, that we’re getting too little “cinema” and too many “movies”. Which he first rather confusingly defines as: “a movie is something you see, and cinema is something that’s made.” As he refines the idea moving forward, it’s pretty clear that he’s talking more specifically that “movies” are mechanically proficient but largely impersonal (by which I gather that he means not just mindless popcorn entertainment, but also Oscar season prestige pictures), while “cinema” is anything made by someone with a clear individual perspective that they want to express, and sometimes that means that they make something bizarre and unwatchable; but only they could have made it, and it’s this idea of cinema-as-private-expression that captivates Soderbergh so much. The terminology is perhaps inapt, but the concepts are sound, mostly because they’re so familiar.

Frankly, it’s this middle sequence of the speech, where he lays out his moral argument, that Soderbergh is at his least interesting: the kaleidoscopic opening has the flow of a great conversationalist holding court over whatever crosses his mind, and the closing has great value that we’ll talk about presently. The middle, though, is nothing we haven’t heard, nothing that wasn’t being said as far back ago as the ‘40s: Hollywood is more concerned with making reliably mediocre product than servicing personal vision, and that’s bad.

Of course it’s bad, on the face of it (though unspoken in Soderbergh’s argument is the idea that just because something is personal and non-commercial, it is also interesting, and this is not inherently true: the aesthetic and thematic homogeneity of the “young urban whites” branch of American independent filmmaking demonstrates that). But the way Soderbergh mounts his argument is perhaps chiefly of interest to Soderbergh himself; the vibe is more “I regret how hard it is for me to make strange little pet projects on studio money now”, and not anything that necessarily applies to someone like Shane Carruth, one of the people Soderbergh specifically name-drops, whose recent Upstream Color, which makes DIY filmmaking part of its texture and theme, doesn’t obviously suggest that he’d take $10 million in Hollywood money even if it was offered.

It’s also not entirely clear what message we’re meant to take from this: that studios are afraid to take risks? That audiences are? The anecdote about how Side Effects couldn’t find an audience certainly suggests that even when the stars align, the people who go out to see movies have been so conditioned to only want to see the biggest, splashiest spectacle, not little character pieces, but outright blaming the audience for being too passive is a level of confrontation Soderbergh isn’t willing to go into, no matter how much it’s the obvious direction of his thoughts.

Certainly, it's not because the white people aren't pretty enough

Everything’s made up for in the stunning final passage of the speech, though, as he begins to sidle from aesthetic concerns to business ones, and lays out, in the clearest examples I have ever heard, exactly why the studios have embraced the salted-earth “summer tentpoles über alles” mindset that has grown increasingly dominant in the film industry over the last few decades and even just the last handful of years. Again, it’s not exactly revolutionary material: since big, expensive sequels reliably make money, the studios focus on those at the expense of more daring and/or smaller productions. But the on-the-ground way that this is all told, with the user-friendly recourse to monetary figures, brings that reality home. It makes not just the size of the problem, but also the intractability of it, comprehensible enough that it's considerably more objective and diagnostic than the mere rant he promised.

All of this is interleaved with strands that Soderbergh doesn’t follow-up, fascinating ideas that I deeply wish he’d explored more: the idea that filmgoers are stalled in a post-9/11 state of escapism, which he forgets about immediately, or his ideas for solving this problem that he’s so expertly identified. The closer the speech gets to its end, the more frustrating it becomes that he relies on such generalized positives in the face of such particular negatives. But this much is true: he’s begun a conversation from a much more analytical and thoughtful place than most end-of-cinema jeremiads are able to, and however vaguely expressed, the ideas he presents are much more worthy of development by filmmakers and filmgoers alike than mere complaints about how shallow popcorn movies have become.

Reader Comments (7)

"Post 9/11 state of escapism?" Okay, let me define it in a reasonable way that I doubt Mr. Soderbergh intended: Post 9/11 state of escapism. Refers to the unfortunate trend of live-action cinematic escapist fiction between, let's say, 2001 and 2007, to have the almost total inability to have strong lightly comedic notes and brighter lighting. Crushed by the growing success of the Marvel Studios films in 2008 and onward, particularly the original Iron Man. (The cracking of the trend was not helped by a massive and still generally infamously terrible pre-9/11 movie that barely broke even called Batman & Robin heavily influencing tonal directions (in a "this is what not to do" way) in the prime mode of escapism, the superhero film.) Soderbergh saying we're still "locked in it" in 2013? Out of touch, or, at least, out of touch with the escapism. Like the makers of bleeping Man of Steel!

I'm 100% on board with you there. Part of the reason I wish it had been dealt with more thoroughly. In general, I think the whole piece suggests that Soderbergh doesn't actually watch many of what he's dismissing as "movies".

Based on your writeup, I was expecting a 'man-yells-at-cloud' kinda deal, but was plesantly surprised at what he had to say, even though what he had to say wasn't necessarily something we didn't already know.

The one point I really agree with him is on the lack of quality 'smaller films.' I think they're still being made and out there, but they're increasingly harder to find, and eventually die out from lack of interest/word-of-mouth; I mean not all of us have access to film festivals.

I also think it's interesting that he mentions the early-to-mid 2000's as a sort of turning point for studios pushing large tentpoles exclusively, and how this is also the same time that all of these really original and well produced dramas started making their way to TV; that can't be a coincedence right?

Great speech, but I kinda tire of this sort of doom and gloom rhetoric. Every year there are great movies made, and some of them DO make money (just last year, Lincoln, Django, Silver Linings Playbook, Life of Pi, Zero Dark Thirty...all great cinema, all rousing successes). It's just that Soderbergh's films rarely make money. Why? He's a very unemotional filmmaker. It's difficult to connect with anything he makes. They're cold.

"Cinema is under assault by the studios and, from what I can tell, with the full support of the audience."

"When you add an ample amount of fear and a lack of vision, and a lack of leadership, you’ve got a trajectory that I think is pretty difficult to reverse."

"So things like cultural specificity and narrative complexity, and, god forbid, ambiguity, those become real obstacles to the success of the film here and abroad."

I support this speech.

MDA -- even when you do have access to film festivals they can kind of be disappointing in terms of quality. I think this is probably a very unpopular truth but there is a reason a lot of films don't find distribution. That said -- it's hard to not be sad when you see something really interesting (even if it's far from perfect) at a festival and you know it has no shot in the marketplace because of The State of The State of... as it were.

Last year gave decisive evidence that the public doesn't just want cartoon epics and effects spectacles, but they want actual humans in human stories. Silver Linings Playbook, LIncoln and the Best Exotic Marigold Hotel raked in the cash without any superhuman powers or supernatural influence. The formula was simple: Tell a good story with real emotion and the audience will come. The problem is that cynical studios and distributors have no patience. All the aforementioned films were slow-builds at the box office. The honchos need to learn how to calm down and finesse the opening of well-made smaller films so they have time to coax the audience in before the DVD bins beckon.