Interview: "Labyrinth of Lies" Director on Obsession, Oscars and How Directing is Like Playing Music

Wednesday, September 30, 2015 at 6:02PM

Wednesday, September 30, 2015 at 6:02PM

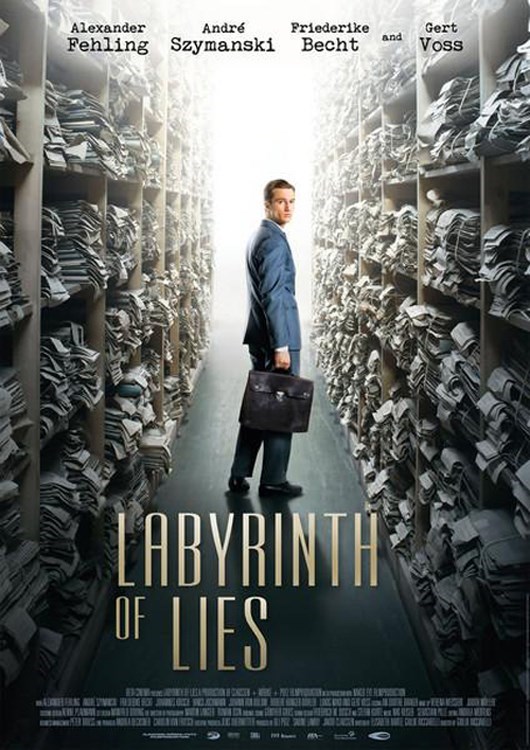

Jose here. When we first meet Johann Radmann (Alexander Fehling) in Labyrinth of Lies, he’s a tenacious, idealistic prosecutor, who refuses to let a young woman get away unscathed from a minor traffic ticket with the notion that the law should be abided no matter what. His world is turned upside down upon discovering that the system he respects so much is overcrowded with former Nazis who were never prosecuted for their crimes against humanity. When his boss Fritz Bauer (Gert Voss) sees his potential, he assigns him to investigate the crimes committed by former workers at Auschwitz. Directed by Giulio Ricciarelli, Labyrinth of Lies is a powerful thriller that touches on the subject of obsession in unexpected ways. The film’s plot spans for almost a decade, which allows us to see the frustration and powerlessness felt by the characters. Even knowing the real life outcome, we sometimes doubt Johann will be able to overcome the corruption and indifference of those in power.

Jose here. When we first meet Johann Radmann (Alexander Fehling) in Labyrinth of Lies, he’s a tenacious, idealistic prosecutor, who refuses to let a young woman get away unscathed from a minor traffic ticket with the notion that the law should be abided no matter what. His world is turned upside down upon discovering that the system he respects so much is overcrowded with former Nazis who were never prosecuted for their crimes against humanity. When his boss Fritz Bauer (Gert Voss) sees his potential, he assigns him to investigate the crimes committed by former workers at Auschwitz. Directed by Giulio Ricciarelli, Labyrinth of Lies is a powerful thriller that touches on the subject of obsession in unexpected ways. The film’s plot spans for almost a decade, which allows us to see the frustration and powerlessness felt by the characters. Even knowing the real life outcome, we sometimes doubt Johann will be able to overcome the corruption and indifference of those in power.

The film will represent German at the Academy Awards, and begins its US theatrical release today. I spoke to director Ricciarelli about his unique directorial style, the theme of obsession and creating supporting characters worthy of their own movies.

JOSE: Labyrinth of Lies is essentially a film about obsession. Can you talk about how you used obsession to shape the structure of the film and the character played by Alexander Fehling?

GIULIO RICCIARELLI: When we made the film there was a big conceptual decision to be very true to the historical facts and take liberties in the emotional journey of the characters. Johann is a composite of three prosecutors and to make that very clear we invented a name for him, because he is borrowing elements from real people. This young man is a symbol of young Germans growing up who were too young to experience the war and went to grow up in an environment of silence, they didn’t know anything about what had happened. So to take him from being a young humanist with very black and white ideals - he sits on a very high moral horse - and to basically have him confront the horrors of the Holocaust and break him down almost completely was the journey. The other aspect of the obsession was Johann’s fixation on catching Mengele, and besides the fact that Mengele was the demon that he was, Johann’s obsession becomes a weakness in his journey. Mengele is pure evil, but to hate pure evil is easy, the whole trial and journey was instead to face what “normal people” had done during the Holocaust. Once Johann realizes the enormousness of his endeavor, he’s fixated on Mengele but that’s the wrong path. When Johann tells his mentor Fritz Bauer (played by Gert Voss) that “Mengele is Auschwitz”, Bauer tells him “no, everybody who participated, and didn’t say ‘no’, they are Auschwitz”.

JOSE: Germany has somehow been more open to discussing Nazism and facing their responsibility than other countries that supported Hitler. When you were doing your research did you encounter any obstacles, such as classified documents or people refusing to talk to you?

GIULIO RICCIARELLI: No, actually, and this is the interesting thing, starting with this trial Germany made the decision to face its demons. Doing the research, shooting in actual locations where the trials were held was possible. What was interesting is that the trial was forgotten, which I found very interesting psychologically, Germany sees itself as a culture of atonement and dealing with the past, but it doesn’t want to see that this started in 1963 through the effort of individuals, but for almost 18 years after the war there was a very concentrated effort to deny this, starting from the government. Konrad Adenauer who was Chancellor and not a Nazi at all, said let’s draw a line below the past, let’s look forward, let’s not look back. It’s time that people like Fritz Bauer get the place they deserve in history.

Giulio Ricciarelli and Alexander Fehling

Giulio Ricciarelli and Alexander Fehling

I found Marlene’s (Friederike Becht) arch to be quite interesting because when the film begins she’s not in control of her own life, her father was a Nazi and she doesn’t know it, but by the time the film ends she’s become an entrepreneur and in the very last scene she’s in we see her wearing pants! Which sounds very superficial, but also beautifully symbolized how far women came along after the war and made me think Marlene deserved a movie of her own. You co-wrote the screenplay with Elisabeth Bartel, can you comment on how the two of you created Marlene?

I come from an acting background so we worked on every character having range, even the bad guy Friedberg (Robert Hunger-Bühler) has a moment of pure love when he says how much he loved his country. I’m glad that you saw that in Marlene, because like Johann she too is part of young Germany on a metaphorical level, Marlene is full of energy, ideas and dreams and she stands for the economic miracle, it’s important to show because people forget how open to entrepreneurship Germany was in the 50s. Because everything was destroyed, everything was needed and people could build something for them. At the end of the film I wanted to show a reconciliation of sorts between the Germany that didn’t want the trial and one that did. Of course in the screenplay we added details like the pants or the bittersweet scene when Marlene realizes her father’s dark past.

Also, at the beginning of the film Johann is listening to the radio and we hear an announcer comment on how women needed permission from their husbands to work, which I thought was crazy!

The law in 1958 said that women were allowed to take a job without permission from their husbands, but they made an amendment that said they still had to be able to fulfill their household duties, so the man was allowed to give his permission or not based on this. We needed to put this in the film because it’s a window into the time.

Alexander Fehling and Friederike Becht

Alexander Fehling and Friederike Becht

From an aesthetic perspective I found it so powerful to see you set the interrogation scenes to music without actual dialogue. We have seen so many films about the Holocaust and know the horrors so well, that to just see these people’s faces recount their suffering made for a more devastating experience. Were the actors actually recounting Auschwitz horrors and how did you come to this directorial decision?

From a directorial point of view I wanted to be as humble and unobtrusive as possible, so they weren’t actually actors, they were extras that we cast for their expressions. I worked extensively with each of them and told them we’d turn off the sound so they could be really open with me. I asked them things, I yelled at them, I asked them to share sad experiences, so afterwards they all came to thank me because they weren’t treated like “extras”. A lot of them really opened up and became really emotional. Like you said there are so many iconic images and films about the Holocaust, and stories the audience already knows, so it was always clear that we didn’t want to recreate the camp with flashbacks, even having an actor in a costume giving testimony felt wrong, because audiences are sophisticated to know it’s an actor and we wanted to refrain from showing directly. We wanted the film to have moments where it turned into a black canvas and the audience can put their own emotions and stories in there. My brother gave me a CD with music from a synagogue in Toronto, so when we were looking for music we used this for the layout and then realized it was perfect. We tried Mozart and it worked of course, but it was inappropriate, it would’ve been also wrong to compose a huge musical score and try to manipulate people into emotions, so we used this very simple, church song.

I felt that the movie could’ve gone on longer because the research felt so thorough, how did you find the “perfect” running time in the editing room?

The truth is you don’t know, it’s like a piece of music. I knew that I wanted people to have a cinematic experience, I’m trained as a stage actor so I wanted the film to always be moving, it had to breathe, but also I didn’t want to take too much space. It’s like playing a piece of music and finding what you think is the right rhythm. I don’t know if the running time is perfect, or how the movie would be without ten minutes. You come to a point in the editing when you feel this is the best you can do. Probably when I revisit it in three years, I’ll want to change some things, but it’s like everything! When do you know a camera move is as smooth as you need it? When do you know an actor gave you the take you needed? Basically you’re just praying all the time (laughs).

Last, the film was selected to represent Germany at the Oscars. Are you excited, nervous?

Of course, the entry made me very excited! While I was waiting for the announcement I turned off the phone because otherwise I would have gone crazy. I turned the phone back on and my producer asked me to call him, by his tone I knew it would be good news. So we’ll see… (knocks on wood)

Labyrinth of Lies is now playing in US theaters. For further reading, check out Nathaniel's review, the Foreign Submission charts, and a visual tribute to its star Alexander Fehling.

Reader Comments (3)

I want to see this again. I don't remember it clearly but at the same time it aged well (???) in my head

I think you liked it even more than I did, but in the weeks since I saw it, I have found myself thinking about it more than I expected (also, I want to own an atelier like the one in the movie, even if I can't sew to save my life)

Thank you very much for this interesting interview! It is fascinating to read about the thought process shaping the movie.