Revisiting "Frida"

Friday, December 22, 2017 at 4:00PM

Friday, December 22, 2017 at 4:00PM by Ilich Mejía

Frida came out in my native Honduras towards the end of 2003, nearly a year after it was released in the United States. Back then, it wasn’t uncommon for Honduran theaters to get films much later, but it was uncommon for them to show anything that wasn’t a blockbuster—regardless of the amount of Oscars or movie stars under their belt. Despite featuring niche themes like political art and unconventional family dynamics, Frida offered Latin American audiences something else: visibility in an optimistic, familiar context. This was not a film about a Latin American drug lord knowingly putting their family’s life at risk to meet wealth or about an immigrant leaving their roots behind to see if the American dream is a real thing: it was the story of a woman trying to make her native Mexico proud, ironically funded by Hollywood to be seen by more without the condescending, stingy distribution of a foreign film.

Salma Hayek stars in the film (that she also produced) as Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. Hayek began her acting career in Mexico as a telenovela and eventual film star. Telenovelas are unfairly immediately associated with melodrama and excess, but these Latin American vehicles should be more known for intelligently catering to women, their core audience. This results in the production of many female-centric, multiepisodic stories that develop its female characters in a three-dimensional way that many American prestige shows still struggle with. Hayek landed her biggest get in Mexico in 1991 as the lead of Teresa, a telenovela about an ambitious, smart young woman struggling to make it in Mexico City. Hayek eventually enjoyed so much success in Mexico that she decided to move on to the next best thing: Los Angeles.

There’s a loud sigh of resentment and suspected betrayal that many Latin Americans let out when our talent runs off to test their success in the United States. Surely because we will miss them, but mostly because we mistrust how welcoming and deserving their reception will be. Stars go from starring in their own empowering films to day playing as stereotypes and it’s devastating to watch. That devastation, however, is placated when stars like Hayek reach fame abroad and capitalize it to bring awareness to their roots. After starring in box office hits like Wild Wild West and Desperado, Hayek cemented her star status and estimated it would help get one of her biggest passion projects, the story of Kahlo, easily made. She eventually accomplished her dream, but not without struggle.

Hayek recently detailed the harassment and unprofessionalism she and the film’s crew had to endure before, during, and after shooting Frida in an op-ed published by The New York Times. Harvey Weinstein, in charge of distributing the film under his company Miramax, was the source of both. Hayek, unknowing of Weinstein’s tactics, was swayed by the distribution company’s prestige and experience with Mexican projects: in 1993, Miramax distributed Alfonso Arau’s Como Agua Para Chocolate (Like Water for Chocolate) and helped it earn a Golden Globe nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. Watching Frida again fifteen years after its release and days after its acrimonious production was brought to light underscored many of the film’s themes and artistic choices while reminding me not enough forces are encouraging projects like this today.

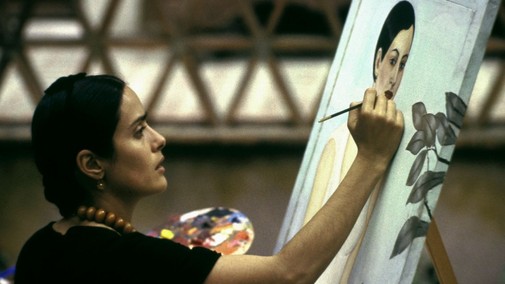

The film, as directed by Julie Taymor, is bright and assertive throughout. Taymor takes on the difficult task of ensuring the film’s aesthetic lives up to its subject’s stylistic legacy—and not just with Julie Weiss’s flawlessly curated costumes. Kahlo’s personal style was often defined by embellished braids, statement jewels, and traditional Mexican silhouettes in bright textiles; a style so distinctive any modern recreation can be instantly traced back to her. Taymor uses this singularity as inspiration as she injects the film with a vibrant score composed by her partner Elliot Goldenthal (Across the Universe) and daring, often unusual cinematography by Mexico’s own Rodrigo Prieto (Brokeback Mountain, Silence).

Taymor also borrows from Kahlo’s approach to art when presenting her subject’s life across many decades. Kahlo’s magic realism seeps into Prieto’s frames even—or especially—in the presence of personal trauma. In an early scene, a teenage Frida (played by Hayek in an already whimsical choice) fractures her spine as gold spinning from a newspaper covers her body and a symbolic, bright blue bird is released from the grasp of its owner to fly over her. Taymor, faithful to Kahlo the artist, refuses to paint hardship as something purely unpleasant. Throughout the film, viscerally painful experiences like a miscarriage and infidelities are adorned by outré elements that transform how Frida faces and chooses to remember her countless hardships. Similarly, the movie’s editing mimics the construction of her paintings, at times too literally, by continuously allowing life to inspire and elevate the creation.

The film successfully depicts the struggle of identity in relation to where we live and where we are from. Mexican culture, never watered down, is luxuriously present in every scene. Stop motion skull interludes, carnival scenes, and lively Aztec remnants firmly set the film in Kahlo’s Coayacán. Every actor (including British Alfred Molina playing Frida’s husband, muralist Diego Rivera) has a thick, English-as-a-second-language accent to show how the characters and makers of the film grapple with embracing international influence and fame without releasing their heritage. Molina’s Diego is most interesting when he’s a foil to Frida’s concept of success: Frida’s fame means very little if it doesn’t resonate with her Mexico, but Diego is desperate to move away and impress foreigners with his political art. The movie poses an interesting question about what we owe our motherland, especially when—like in left-wing Diego’s case—it repulses your way of thinking and living so tenaciously.

Equally interesting—and timely given Hayek’s recent account of the film’s journey—is its depiction of struggle and perseverance. The film is set during the rise of the Mexican muralism artistic movement. Artists like Rivera and José Clemente Orozco depicted strong sociopolitical messages on public walls with massive, statement murals. Kahlo made her art more personal and intimate, specializing in self-portraits and eccentric scenes that were initially met with disdain when compared to the ostensibly more pressing political murals of the time. In the film, Frida is often enveloped in body casts and braces that restrain her movement and complicate her process. That doesn’t stop her from creating some of her most inspired work, and neither does Hayek’s Weinstein. Frida struggles with a similar monster in Diego, whose temper and disloyalties mirror Weinstein’s abuse of power and make Frida (and the viewer) wonder how much one can get away with when backed by talent and power.

The film is hardly perfect: its script is loaded with too much expository dialogue and many characters, like Frida’s money-obsessed mother, are poorly drawn. Its importance transcends its craft, however. Its feat is its effort; one that should be recreated more often than it is given our current climate. It’s a wonder to watch the film tell off anyone that wanted to redirect its gaze. In a later scene, Diego is drawing a model for one of his works and Frida interrupts to tell him his drawing of her tits “lack gravity”. It’s just one example of a wink of empowerment that film gives off that’s eventually echoed by an anti-imperialist rant that cries “the town united won’t be beat”. Nope, not on Hayek’s watch.

Frida,

Frida,  Salma Hayek

Salma Hayek

Reader Comments (7)

I'm really happy to see a positive take on Frida! Thanks for your great post. It's nice to hear about this movie from a Central American's perspective. The film certainly has its issues, but I don't think North American viewers always appreciate how infrequently we get to see this side of Mexican history. Your examples of what we normally see in movies and television are spot on.

This is a great movie as I think it is definitely a crowning achievement for both Hayek and Taymor. It's a shame that it nearly got ruined by Harvey Scissorhands who really needs to be castrated.

Meh ist still as bad as it was back then. And Hayek is horrible in it IMO.

Hayek is terrible in this. She should have produced and taken Judd's role, because there's no way she is a convincing Frida. It'd help if they had made the movie in Spanish.

Salma Hayek is wonderful in this. Period.

Salma was good in the movie. The film has flaws but is also so beautiful.

This film came out when I was like nine, so by the time I got around to seeing it, I'd heard so much about how terrible Salma Hayek is in it that I couldn't even formulate my own opinion and I honestly have no idea if she was good or bad. Maybe I should rewatch.