Review: "It Comes at Night"

Friday, June 9, 2017 at 10:15AM

Friday, June 9, 2017 at 10:15AM  by Chris Feil

by Chris Feil

After last year’s Krisha, Trey Edward Shults returns to the horror of family dynamics with post-apocalyptic nightmare It Comes At Night. This time he’s equipped with higher production value and more familiar faces than that astute micro-budgeted debut, though Night is just as personal. His resulting sophomore feature is part Greek tragedy, part vague social polemic, and one of the most terrifying films in several years.

Set in a remote, wooded mini-mansion, a family has made their home a fortress from some unspecified apocalypse. The elderly father of Sarah (Carmen Ejogo) has fallen “sick”, leaving her husband Paul (Joel Edgerton) and son Travis (Kelvin Harrison Jr.) to dispatch of him for their own safety. The desperate invasion of another family (led by Christopher Abbott and Riley Keough) tests both the reclusive family’s empathy and rigorously protected lifestyle. Meanwhile, Travis is having increasingly vivid visions of the encroaching malignant threat that test his (and our) sense of reality...

Shults has made a strong step forward thematically here, as cosmically unsettling as his debut and then some. His work is fascinated with “me vs. them” mindsets, the agonizing intimacy of his first feature still present here as his point of view shifts from the outsider to the dominant force. This is the family unit on the inside looking out, with only paranoia and distrust to be found until the walls close in around them. The timeliness of Shults’s study on the toxicity of social insularity is smartly underplayed, but unnervingly felt.

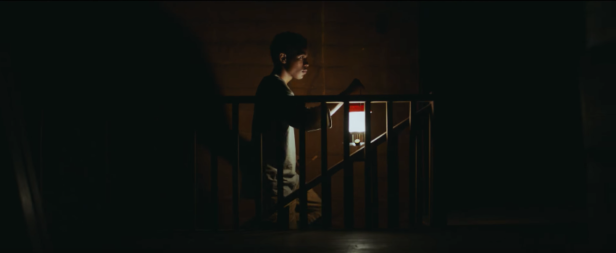

In addition to that increased narrative ambition is an equisitively crafted hellscape of a visual experience. With cinematographer Drew Daniels, Shults captures spacial specificity with the disorientation of a nightmare to maximum chilling effect as he wanders this dark house of horrors. In a slight tilt of the camera or rising hum of Brian McOmber’s score, the film breeds your suspicion of the house and its residents. Like The Shining’s twins or The Witch’s Black Phillip, Shults has made one instantly fear-inducing static image in the home’s red door.

Night allows the ensemble to breathe within the exactingly wrought atmosphere, and a handful of lengthy subdued dialogue scenes maintain a humanity that lets the film sink in beneath the surface. Kelvin Harrison Jr. is emotionally fraught against a stoic Joel Edgerton, father and son smartly drawn with a refusal to present either as irrational. Though the film finds most of its compassion when it includes Ejogo and Keough, it frustratingly keeps them on the sidelines. The film misses something key by excluding them for a few stretches, embodying the role of maleness in isolationism rather than condemning it like it seeks to.

Night also slips somewhat as it spirals into a denouement that slightly betrays the thoughtfulness of its execution elsewhere and the nuance of its allegory. If Night gets under your skin and grabs you by the bones for most of its runtime, then the utter shrieking severity of its final moments unwittingly loosen that grasp.

What lingers after the film has ended, is not the deeply unnerving frights that Shults conjures, but the ideas and questions that settle in your mind - about family, about cultural myopia, about what we deny ourselves when we lose compassion. The film doesn’t reach for the level of cultural incisiveness the likes of Get Out, but it is a horror film that engages with a growing social isolationism and its inherent perils.

Under the surface of Night’s dark hallways and tense silences lay curdled notions of what family means and the fallacy of trust within. It’s a nail-biter of internal and external horror, captivating as it traps you in a cage, turns off the lights, and rattles you.

Grade: B+

Reader Comments