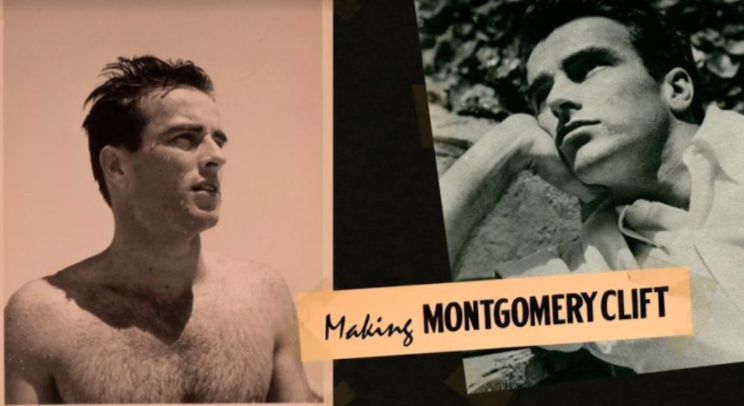

Monty @ 100: The recent documentary "Making Montgomery Clift"

Monday, October 19, 2020 at 4:00PM

Monday, October 19, 2020 at 4:00PM by Sean Donovan

As a kind of epilogue to our Montgomery Clift Centennial series, in which we revisited every film of his, let's discuss a curio that made the festival rounds in 2018 and 2019. The documentary Making Montgomery Clift was co-directed by Hillary Demmon and Monty’s nephew Robert Clift. Robert is very much foregrounded as a protagonist of the film as he attempts to do much of what the Film Experience team has been attempting over the past two and half weeks: to grapple with the legacy of Montgomery Clift and bask in the immortal work he has left behind. Making Montgomery Clift is an imperfect project, and those imperfections arise out of an enormous emotional attachment to the subject that can’t hep but obscure our view of the man and his work.

Making Montgomery Clift provides an overview of the star’s life and career trajectory, the highlights and lowlights that have been gestured to in posts throughout this series: Clift’s struggles with alcohol and pills, his queer sexuality, the traumatic car accident that transformed his career, his reputation as a difficult diva of a movie star, etc. But the film also does the invaluable work of tracing the discourse of our pop culture knowledge of Clift himself: when and how the legend of Monty Clift was written...

The Clift family are storytellers themselves. Through Robert we hear of his deceased father (and Monty’s brother) Brooks, a habitual collector and recorder who has left a wealth of an archive related to his legendary brother. We hear about Brooks and the family’s experience both consulting with, and having their words twisted by, biographers and writers looking to craft the latest version of the Montgomery Clift tragedy. First came a homophobic biography by Robert LaGuardia in 1977, placing the ‘blame’ for Clift’s sexuality on the pop-Freudian stereotype of an overbearing mother (not unlike some queer male characters that graced Hollywood screens in Clift’s lifetime: Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train, or the ultimate king of gay mommy issues, Anthony Perkins in Psycho). Second came a more measured biography by Patricia Bosworth in 1978 that nonetheless failed to meet the family’s standards of a ‘true’ depiction of Monty. The Hollywood rumor mill is referenced and depicted extensively, as the likes of Hedda Hopper, Deborah Kerr, and John Huston all spread different accounts of the supposed chaotic madness that was Montgomery Clift’s life. The film paints a portrait of a man who clearly had little control over what people said about him, and had to live a life of celebrity scrutiny alongside this weight of the public’s pre-ordained ideas and storylines. Robert Clift states early on in voice-over, “This isn’t really a story about a man. It’s a story about what his life was allowed to mean.”

Who was the real Montgomery Clift, and how do we find him amongst all the buildup of discursive distraction? Making Montgomery Clift issues a lot of corrections to the historical record. For instance, Montgomery Clift is often grouped together with Marlon Brando, James Dean, Shelley Winters, and other innovative actors of his time period as ‘method acting’ devotees of Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler. Clift is, in fact, on the record as not believing in method acting. The hype around his Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) performance insisted Clift had a mental breakdown on camera, that part of the power of that performance is that it wasn’t acting. There is no real evidence to support this, and Clift’s strenuous rituals of preparation and performance, at work on the Nuremberg set, fully suggest otherwise.

But other ‘corrections’ in Making Montgomery Clift left me with a more ambivalent response.

Multiple voices in and out of the Clift family assure us Monty was “not closeted” which is true, if complicated. To the larger public Clift’s celebrity was ‘closeted,’ but he lived a life full of love and sexual exploration in the queer subcultures of Los Angeles and the world. The family assures us Monty was funny, cheerful, exuberant- constantly cracking jokes or throwing parties, far from the sob story of repressed gay tragedy we have heard. While Monty’s life was certainly not lived in constant self-loathing and depressed isolation (life is long and complicated!), the family’s repeated insistence on his happiness starts to sound evasive and defensive.

Montgomery Clift lived in a very homophobic and pre-Stonewall world. The financial security stardom provided him and his own resilience were undoubtedly balms against some of homophobia’s worst cruelties. But is it so wrong to allow Monty the space to cry, even after death? Every step the film takes seeks to shore up Montgomery Clift as a brilliant genius, a cunning career strategist, and a radical who didn’t care what the industry or anyone else thought of him. Isn't it possible all of those things can be true, AND Clift lived a life deeply marked by being an outsider in a heteronormative world?

The film recounts a story of John Huston and Clift’s bitter relationship on the set of Freud: The Secret Passion (1962), and despite clear evidence of Huston’s bigotry (the director is quoted by his own biographer saying “I can’t say I’m able to deal with homosexuals,” and describing Clift’s love life as “simply revolting”) the film actively downplays homophobia as a factor in Huston’s hostility, Robert Clift pinning it instead on a dubious argument of professional jealousy. Throughout the film we are told Monty did not suffer from “some massive internal conflict,” and while the truth of Monty’s inner life is inaccessible to us as an audience…how do they know either? Making Montgomery Clift is clearly well-intentioned with mountains of love for its subject, but in these moments I can’t help but think of the many biological families who don't realize the extent of their own distance from the quiet isolation of their queer children.

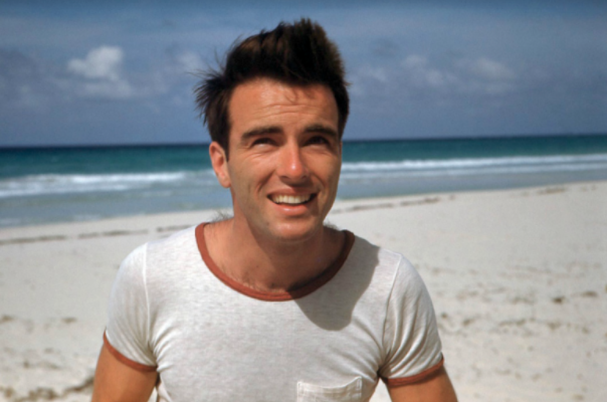

Monty in Fire Island Pines

Monty in Fire Island Pines

Queer men are complicated beasts of contradictory emotions, speaking for myself anyway. The Clift family at times equates Monty being “not closeted” with a life free of lingering forms of self-doubt, depression, inadequacy, and discrimination related partially, if not completely, to the state of being queer in a heteronormative world... which is simply not true. We hear the Montgomery Clift of the mid 1960s in recorded telephone conversations with his brother, with visible signs of drunken slurring, emotional outbursts, stammering, and profound insecurity, evocative of his Nuremberg co-star Judy Garland’s self-tapes of a projected memoir analyzed by Karina Longworth on her podcast "You Must Remember This". To a cruel viewer eager to delight in Hollywood degradation these are signs of the corruption of stardom, the tragedy of gayness, or whatever other old plot trajectory they’d like to force Monty into. And I respect the film’s attempt to work against that. But isn’t standing in ignorance of queer sadness just as dangerous?

Brooks Clift is quoted in his protest to the Bosworth biography, in effect summarizing the problematic thesis of the film itself, that we “need to consider the man as the devoted artist he was, rather than as such a psychological mess.” But we can do both. We can honor the brilliance of his acting and acknowledge the ‘mess’ of Clift’s life that is as undeniably human. We can consider the residue of a star who articulated queer masculinity on screen and in public when it was a thoroughly dangerous thing to do, and that he may have suffered the social, psychological, and emotional consequences.

Lorenzo James, who has been variously described as a butler, personal assistant, nurse, and lover to Montgomery Clift by different biographers and writers, neglects to appear on-camera in Making Montgomery Clift but recorded some brief audio interviews with the directors. Much of Lorenzo’s role in Monty’s life remains murky and unexplained, clearly at Lorenzo’s wishes, and the film doesn’t attempt to pin him down. We hear biographer Patricia Bosworth, in a contemporary interview for the documentary, refer to him as “the black male servant” which feels stunningly cold and cruel in contrast to the director Robert Clift referring to him as “an uncle,” suggesting a warm and intimate relationship. And it is Lorenzo who speaks most poetically of the queer beauty and joy of Monty’s life that we rarely got to see: “the medicine that Monty was brewing…it gave off a glow.” The credits indicate that Lorenzo James died shortly before the completion of the film, leaving him, like Monty, to the space of queer history accessible only in recorded translations, with all their limitations.

If attempts to remember Montgomery Clift are always marked by these issues of translation and who is doing the translating, how can we best pay homage to legendary figures like him? I would suggest we do much what The Film Experience has been been doing and stay with his work, allow it to cherish and nourish us, and accept with gratitude the trace of the glow we are lucky to observe.

Series Index. Thank you for sharing the journey of this all-film retrospective with us

Reader Comments (10)

I just bought he dvd after this review.

Sean -- love this post. I think it's an interesting piece, especially since we embraced the common reading that this particular movie is fighting against (about his tortured life). I'm always highly suspicious of family members making movies about a famous person due to conflict of interests at getting to the truth BUT i am alarmed that I've never seen this and I shall correct the omissions.

This is a really lovely post.

Wishing to echo Nathaniel and Arkaan- what a lovely read

I really liked this documentary. It was really amazing to see and hear all that archival footage, interviews and all those photos. I also liked how it gave a second thought to the beginning of the mysteries of Clift’s “tragedy” and an alternate way to look at it. I’ve seen Bosworth’s biography referenced a lot in articles and such as being a definitive source, but after seeing the issues his family had with the final result, I can try and keep an open mind when I finally get around to reading it.

Monty's twin sister turned 100 two days ago...

I also thought watching this that MC was probably more complex than any biography until now (written or filmed) has been able to capture. He may have lived as openly as possible given 1950s morals, but I'd be surprised if he didn't experience some amount of anxiety as a gay man trying to make a career as a leading man in Hollywood. I appreciate how this documentary rejects the notion that his bisexuality implied that he was somehow cold, withholding or otherwise less than a giving partner to those he was involved with.

Hearing his brother's voice answered a question I've had for a while, especially during the post-accident films. So Monty really did talk that way—it wasn't just an affectation. Brooks sounded just like him!

Please - what is meant by "cunning career strategist?" He seemed to be highly dismissive of a number of possible roles that came his way. His rejection of "Sunset Boulevard" was a great disappointment. If he had been open to it, I think he could have taken over the Edmond O'Brien role in D.O.A. Clift also would have been an interesting Shane. If he had been allowed the closing act on his career how about these post-"Reflections" possibilities - "The Heart is a Lonely Hunter," "The Owl and the Pussycat" (with Liz), the Peter Finch role in "Network," and the Gregory Peck role in "The Omen."

Thanks for reviewing this one. I saw this last year and liked it but with similar reservations if I remember correctly (it's certainly better than the doc about another of Nathaniel's faves, Natalie Wood, that was out earlier this year).

Nice overview and wrap-up. Haven't seen this yet but looking forward to it when I get a chance.

Loved the entire series.

I am both moved, and troubled by this post. What was fascinating about "Making Montgomery Clift," is that it challenges the dominant narrative, in a pretty compelling way, by suggesting that you cannot reduce a man to just one thing, one identity.

The film did address the homophobic time he lived in, and explained that gay men could be arrested ,and their lives ruined. So I don't think it dismissed the power of homophobia.

IBut Monty hated labels, which is both a natural position for such a great actor: you have to be comfortable inhabiting all kinds of characters. There are many plausible causes for the difficulties he had: homophobia, illness (which, according to a physician, made him appear drunk, even when he wasn't), an uprooted childhood, and just being human and prone to the usual trials and tribulations of life. I cannot help if we're not, yet again, imposing another narrative on his life: that of the sad gay man.