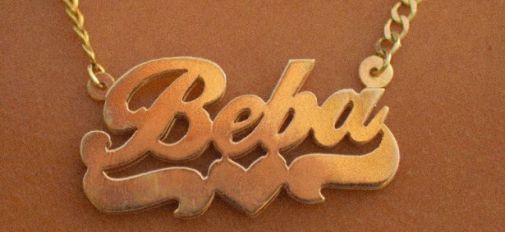

Doc Corner: Rebecca Huntt’s 'Beba'

Wednesday, June 29, 2022 at 3:00PM

Wednesday, June 29, 2022 at 3:00PM By Glenn Dunks

That Beba is the work of a first-time filmmaker is both immediately impressive and also quickly apparent. There’s a maturity here that belies Rebecca Huntt’s autobiographical documentary portrait. It’s something that leaps out from its opening moments as flickering 16mm photography plays over poignant narration. “Violence is in my D.N.A.”, she says. “I carry an ancient pain that I struggle to understand.” It’s powerful stuff, but as it progresses, Huntt’s film finds itself swaying in the wind despite the really great stuff at its core.

That maturity is often balanced by selfishness that renders itself with a film that is unfocused almost as if by design. Huntt is a messy, complicated person; something that this movie impresses upon the viewer frequently. Whether it’s as a result of her family or society—most likely a strong dash of both—is something that the movie attempts to grapple with.

Huntt does that grappling through interviews, confessionals and some frequently sublime visual poetry. It doesn’t necessarily all work, but like Huntt the subject, Huntt the filmmaker is likely a work in progress.

“Beba” is the nickname given to her by her mother. Beba is the movie she has made to explore the identity that was building before she was even born. Her father migrated to America from the Dominican Republic, landing in Bed Stuy in the late 1960s. Her mother is from Venezuela, the child of a woman with schizophrenia as well as an acute business acumen (both of which are seemingly quite relevant to Beba’s story). She gets along with her dad much more than her mother who appears to treat her child with the hardened energy of somebody who struggled and fought and who thinks her child should have to as well (as the film goes on, however, it becomes less black and white around who exactly the aggressor in that relationship is). Huntt’s sister is what would be called ‘troubled’, and her brother (unseen on camera outside of old photographs) is temperamental to the point of sabotaging a job interview for Rebecca out of seemingly nothing but spite. At one point the filmmaker criticises her mother for her “micro-aggressions”, but this is a family built around them. A mixed-race family that, for Huntt, has left her unmoored in multiple ways.

This is, of course, only emphasised by the world that exists around her. Her family have never been able to afford an apartment with more than one bedroom. They grew up at a time when white gatekeepers of their neighbourhood would literally keep them out of spaces that would have aided their development. And as she has braids worked into her hair, news reports detail the daily racism that is inflicted upon black people in America.

It's all very heady stuff, and Huntt deserves praise for going there and addressing it so forcefully. Technically, she has assembled a crew that work wonders. Holland Andrews in particular has made an excellent score, something that intertwines with a sonic landscape that often sets out to deliberately discombobulate and set an audience off centre. Sophia Stieglitz’s cinematography, too, impresses, particularly in the warm, bright colors she is able to achieve through the use of 16mm.

But Beba suffers from a certain storytelling aesthetic that is hard to avoid. Stieglitz’s work switches mediums for reasons that remain uncertain, across four chapters that feel sporadic. In another moment, a confrontation between Huntt and her white friends comes across as oddly out of place—it turns out to have been scripted. Again, for reasons that remain uncertain beyond, I suppose, Huntt wanted something of its effect that she wasn’t able to capture. But most notedly, it is Huntt’s narration that while occasionally landing upon nuggets of truth and gold (like that opening), also throws up some real clangers. It is like being given unfettered access to a diary with all that that entails. There are moments that are painful and punctuated with anger. There are others that sound like somebody reading the first draft of a book of poetry. At times it even struck me as the kind of project you would see in a satire about film school wonks.

The friction she is able to create is admirable and as a work of cinema, there’s a lot of recommend. I hope the director got out of making Beba what she hoped to. I’m not exactly sure I know what that is, but I appreciate being let into this part of it and to see something so unfiltered from this type of personality within this culture. I am curious to see what she could produce next with the sort of storytelling maturity that can come from getting something so extremely personal out of their system.

Release: Currently in limited theatrical release.

Awards chances: This isn’t normally what the Academy’s doc branch go for, but I can see some critics groups and particularly a group such as the Indie Spirits appreciating what Rebecca Huntt has achieved.

Doc Corner,

Doc Corner,  Review,

Review,  documentaries

documentaries