The haunting beauty of "Kwaidan"

Saturday, April 8, 2023 at 12:41PM

Saturday, April 8, 2023 at 12:41PM

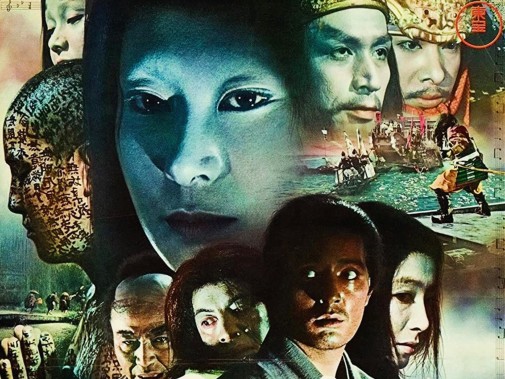

This month, in the Criterion Channel, there's a spotlight on Kwaidan, the Masaki Kobayashi classic that became the first significant example of Japanese horror to reach international audiences. You can find critic Grady Hendrix exploring the 1964 anthology on the streaming service, but that's far from the only reason you should check it out. Kwaidan collects four ghost stories that, together, form cinematic poetry of ravishing beauty. No wonder Kobayashi's film has entranced The Film Experience for years. Dancin' Dan once wrote about Kwaidan for the Oscar Horrors series, Nathaniel and Juan Carlos discussed it in podcast form, and I highlighted its costuming for an idealized Oscar ballot.

Still, it's never a wrong time to re-consider Kwaidan, to get lost anew in its visual splendor...

So, let's do that, pouring over a collection of shots that showcase the work of cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima, art director Shigemasa Toda, and costume designer Masahiro Katô. Hopefully, if you haven't seen the film, this will convince you to try it a try.

Adapted from the work of Lafcadio Haren, who, in the early 1900s, recorded Japanese folktales in print for the first time, Kwaidan divides itself into the aforementioned four tales. Each vaguely represents a season, adding a tinge of natural order to its quartet-like structure. But nature will also be repudiated by ways of obvious falsity. Every frame a painting, the film glows with deliberate artifice and a touch of theatrical flair. Nothing looks real, and even the few glimpses of a world outside the soundstage (actually a repurposed airplane hangar) appear framed in Tohoscope to evoke the sense of stagecraft.

Kwaidan further represents a departure for its director who had, until then, made his name with scorching pieces of political cinema, dramas ignited by outrage and flames of fury. Here, the realism of those first films is sacrificed at the altar of ancient tradition, bringing mechanisms of Japanese theater and centuries-old storytelling to the forefront. That includes interpretative choices. Regard the actors who move across these spaces as something more than precise Noh thespians. They're akin to bunraku puppets manipulated by the master filmmaker into the correct poses. It's beautiful but inhuman, for beauty itself is a conduit into the other world.

Not that you'd know that right away. For what, in 1964, was the most expensive Japanese film ever made, Kwaidan starts with surprising humility and not a hint of scenographic lushness. In its place, we get ink spilled on water, dissolving like plumes of smoke in the atmosphere. From black, we move to color, announcing the importance of chromatic expression in the ensuing picture. So, fittingly, the first story has a color in its name, though it's that of china ink rather than rainbow silk.

"The Black Hair" revolves around the ambitions of men who look at women as stepping stones in their path, a social critique comprising a rhyme of two marriages.

Architecture plays a central role, crystalizing the idea of time as a cruel touch that decomposes everything it comes across. And yet, better to be a fragile thing ravaged by time than to be cold and unmoving, for there's another, different cruelty to that which denies the effects of time. There's more comfort in an abode turned haunted house than the pristine quality of a nobleman's space. In the end, eternity is the place of madness. And in a trance, we learn these lessons, lulled into hypnosis by a measured cadence, stunning sights.

As we continue the folkloric travails to another story, eyes glow in the sky, bitter winter personified by some cosmic gaze, maybe Kwaidan's most memorable special effect. On other occasions, the backdrop will become even faker, a sunset defined by juxtaposed rectangles like blocky brushstrokes. Kobayashi's training as a painter is in full bloom, exposed all across the screen.

"The Woman of the Snow" is a tragedy of male weakness, perchance masculine arrogance, for it hinges on a man who shatters his happiness simply because he can't control his curiosity, his mistrust. Broken vows echo through all these tales, of course. This one starts in deadly chill, as two woodcutters venture into the forest where they meet a yuki-onna, later developing into a golden romance destined to ruin.

Midorika Michio was the picture's color consultant, collaborating with the directors and other creatives to formulate the movie's masterful look. No other chapter showcases their genius better than this second one, where the fire of dusk, the cold yellow of winter sun, and the variable blues of spectral apparition turn the screen into saturated watercolor. Indeed, the advent of azure light defines the horror in the tale, breaking bliss with a kiss of death beyond dying.

"Hoichi the Earless" is the third chapter and practically a feature framed by short films on both sides. Moreover, it touches on themes familiar to whoever has recently watched the animated marvel that is Inu-Oh. It's the story of a blind biwa-playing monk haunted by otherworldly voices. They are the ghosts of the Taira clan, defeated in maritime battle by their enemy centuries before. Every night he is taken to the beyond, playing for the spectral court in the film's most apparent wink toward stage tradition.

It's the disruption of theatrical geometry that invokes true horror, cadavers messing up the lines, dancing flames cutting across the frames within frames. When blood is spilled, it's another disruption to the rigorous mise-en-scène. You see, despite belonging to the horror genre, Kwaidan doesn't mean to scare its audience. It wants to unsettle, however, suggesting the existence of two worlds - that of the flesh and that of the spirits. They should never mix.

Finally, "In a Cup of Tea" takes place much later than all the later stories, coming closer to the 20th century than any of its brethren. It's also the shortest and most beholden to meta-textual readings, being about a folklore researcher vexed by the fragmented nature of the stories he studies. Logically, the tale told is incomplete by the director's design, twisting itself around a more realistic visual language only genuinely violated by stylized light. And so, to gaze into Kwaidan is to peak into the abyss, into the darkness of the beyond, that beautiful beyond.

Are you a fan of Masaki Kobayashi's Kwaidan? If so, what's your favorite of its tales?

Reader Comments (1)

I saw this a long time ago on TCM and whoa... it is just an immensely phenomenal film. There's nothing like it before or since.