The Matrix @25: Queering the Canon

Sunday, March 31, 2024 at 9:00PM

Sunday, March 31, 2024 at 9:00PM

Happy Easter! Happy Trans Day of Visibility!! Happy 25th anniversary to The Matrix!!! As luck would have it, these three occasions coincided this year, making for a lovely little cinematic celebration. After all, The Matrix is probably the most famous work by trans filmmakers – the Wachowski sisters – and Neo's journey can be seen as an allegory of gender identity. It was somewhat devised as such by its closeted auteurs who've reclaimed their work's intrinsic queerness after it became a powerful reference for the MRA movement and the alt-right. Like many misappropriated movies, The Matrix doesn't deserve its fans. Or, perhaps more accurately, a good portion of its fandom doesn't deserve The Matrix in all its glory.

But Neo isn't just a queer icon. He's also something of a Jesus figure, a Messiah for our cyber-noir future, bedecked in fetish fashions, armed with kung fu moves and impossible firepower. And like Christ, he is risen…

The Matrix was all about the desire for transformation, but it was all coming from a closeted point of view.

Lilly Wachowski said that while discussing The Matrix with Netflix in 2020, four years after coming out as trans. Her sister, Lana, had already been out since 2010, though rumors had circulated in Hollywood for about a decade by that point. At the time, these declarations seemed to confirm queer readings of the movie long fostered by the community and beautifully articulated by trans critics like Emily St. James, among many others. For those yet unconvinced, consider the necessary push towards that perspective as a corrective to the many years when The Matrix existed as a radicalization tool for the alt-right and other subsets of queerphobic, women-hating white supremacists. Even today, the phrase "red pill" carries with it a cloud of toxicity.

Funnily enough, in the 1990s, estrogen pills taken by trans women going through hormone therapy were a deep crimson, almost maroon. Taking the red pill could be interpreted as the first step toward transition. And even if that wasn't an explicit reference on the Wachowski's part, one can't just dismiss the connection. Consciously or not, the filmmaking pair did as artists have done since the beginning of time, their secret selves finding a way into their work. And like taking the red pill proffered by Morpheus, once you start seeing The Matrix through a prism of queerness, it's impossible to revert back to before. Suddenly, it becomes an obvious artifact of queer cinema, its anti-normative ideas plain to see in everything from script to style.

I think any kind of art that you put out into the universe, there's a letting go process, because it's entering the public dialogue. I like that there's an evolution process that we, as human beings, engage in art in a non-linear way. We can always talk about something in new ways and in a new light.

So said Lilly Wachowski, and so it is, both for the incels who consider themselves trapped in a Matrix-like gynocracy and quasi-sane queer cinephiles like yours truly. Indeed, trying to re-examine the movie in those terms, I pondered the specific impact cyber spaces can have in the coming out process. There's a sense that one can experiment in the virtual sphere and try on things that would be impossible within the bounds of flesh and bone. Queer kids who grew up with the internet already widely available may have first identified their own queerness in those worlds. In the safe space of virtual anonymity, you can sometimes be more yourself than outside of it, just like it's often easier to be honest with a stranger than with those who matter most. At least, I recognize that lived experience.

As if confirming that interpretation, we have Switch. In early drafts, the Wachowskis had devised a character who would be a man in the real world but inhabit a feminine identity within the Matrix. It would have further complicated the desire/revulsion the entire project feels towards its particular hellscape, but it would also make more apparent the queer themes lying just under the surface. Warner Bros. put their foot down, excising that part of the character we'd come to know as Switch, played as a woman in both worlds by Belinda McClory. One wonders if incels and Nazis would have flocked to The Matrix's imagery if the Wachowskis' original intentions had come across loud and clear, unavoidable. Then again, that might've precluded it from being a 467 million dollar hit.

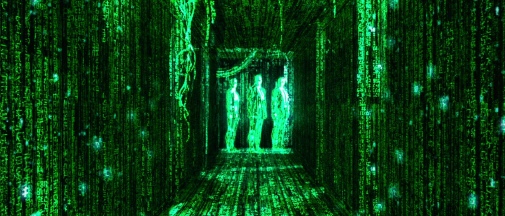

Let's consider further that other paradox. It's always interesting to note how much of The Matrix's most show-stopping visuals derive from its virtual setting's infinite potential. While the machine-made unreality is something the characters yearn to escape, the movie can't wait to dive deep into that mind prison. In some ways, The Matrix works within escapist idioms and cinematic models. Still, it couches that wonder in the disquiet of a story where those very marvels are inherently insidious, the product of unspeakable evil. The monster is a nightmare and euphoria, all mixed into one potent cocktail that, like a Molotov, will set you on fire. It also sets the stage for the director's genre-hopping.

Follow the white rabbit.

The Matrix hops through genres as easily as it hops between worlds. Like gender, genre shall be transformed.

In that regard, the movie is the white rabbit that Alice chases down its hole. However, instead of going down that path to wonderland, Neo does it to find reality. He leaves his quotidian of noir tinted green to come into a bluer environment that's more wasteland than Eden. These contrasting palettes and lighting schemes orient the spectator across the different planes, though they'll later bleed together. After coming out, Neo's view of the Matrix is forever changed, and so is the way changers perceive and regard him. What was sickly but commonplace becomes alienatingly colder, harsher, while the heroes' skintones recover some life we didn't know they had lost.

But the shadows remain, as they always do in noir. The movie's cinematic inspirations don't end there, mind you. It owes much to the Hong Kong action cinema popping off over the last two decades of the 20th century. As a matter of fact, I doubt The Matrix would have its characteristic mix of martial arts and gunplay if not for the world of "Gun Fu" devised by artists like John Woo.

But then, The Matrix's coolness is also why its legacy remains so tainted. Its adherence to action movie precepts, violence unbound, is a potential spark that sets a gunpowder barrel aflame. It's hard to argue against those who accuse the Wachowskis of glorifying indiscriminate gun violence, putting forward an ideological justification for the most destructive anti-social behavior imaginable. An allegory of trans liberation from closeted artists can thus become a weapon of those seeking to oppress them in the first place. The Matrix's coolness is both a formidable achievement of cinema as spectacle and the largest crack in its ideological foundation. In any case, the film is always more interesting when it explores possibilities of virtual combat other than guns and explosives. There are more ways to be cool than to open fire.

I thought you were a guy – Most guys do.

Never underestimate the power of casting and a sleek styling job. Keanu Reeves' good looks are legendary, but few films have explored his physique's elvish qualities, the prettiness of his face, quite like The Matrix. He convinces as both the prototypical everyman and the Chosen One, a figure of immense banality who can turn into something more mystical, beyond the barriers of traditional presentation. The same can be said for Carrie-Anne Moss's elegant hardness as Trinity. The actress' characteristics are made more apparent by gelled hair and butch chic outfits that often make her look like she and Reeves are two sides of the same androgynous coin. It helps that so much of their wardrobe originates in the trends popularized in the recesses of bondage clubs and queer subcultures.

Trinity, in particular, is like a lesbian fantasy with a cyber-noir twist, clearly envisioned by the two women who made Bound their debut feature. Her costumes have a fetishistic quality to them. They're wildly impractical for the action scenes yet transmit a sense of beautiful unreality. Furthermore, all that rubber and vinyl, black shininess everywhere you look, isn't just a kinky gesture. It is also a beckon for the viewer, a tactile siren call. It's as if the screen is reaching out, begging for the audience's curious touch. You can imagine your hands roving over those bodies tightly wrapped in a synthetic second skin, the textures herein. And so, the fashions are body conscious, rendering anatomy into an oil-slick sculpture, aspirational and seductive, a conundrum of queer desire manifest.

It's not only a matter of looking perfect for their roles, of course. Reeves, in particular, is a fantastic vessel for what his directors have in store for Neo. Like a blank canvas, one senses that there are no limits to what one can project or create with him as the foundational base. He'll sustain any madness, and his demeanor – often considered stoned or sleepy – is ideal for a man who must wake up.

What you know you can't explain. But you feel it. You've felt it your entire life, that there's something wrong with the world. You don't know what it is, but it's there, like a splinter in your mind...

Morpheus says everyone is born into bondage, a message that can take dark connotations if interpreted as a decree against other people or a confirmation of superiority. But what if one interprets societal bondage as the prison of gender expectations as perceived by someone whose physical sex doesn't match their identity? The office cubicles Neo works in at the beginning are a prison of boxed-in cis-heteronormativity. To escape them is to run toward something more dangerous but also more fulfilling and alive. Fittingly, every time we're reminded of who Neo was within that environment, it feels like a violation of his new self – his true self. That's where the character's names come into play.

The rebels who form Morpheus' crew have long ago shed the names given to them by the Matrix. Their civilian identities are dead names, so "Thomas Anderson" becomes Neo and never looks back. Noticeably, Agent Smith wields Neo's deadname like a weapon, every utterance a finger's jab into an open wound. In the interrogation room, this aggression is literalized when the Agent's tactics go beyond the simulation's rules. A mouth melting to prevent speech, a bug crawling inside the victim's body – all violations that accompany the deadnaming and help inch The Matrix closer to a territory of body horror. Considering that subgenre's history, such a move forms an even sturdier bridge connecting this action extravaganza to notions of New Queer Cinema.

And like such artists as Haynes, Jarman, Araki, and Dunye, the Wachowkis know how to use cinematic fakery to show something realer than real. Talking strictly about the movie's aesthetic properties, consider the late '90s CGI and how it becomes more and more noticeable as the plot unravels. There's a chintzy quality to the effects, and that helps The Matrix's heroes and audience recognize and accept that a thing's fantasy is a key to unlocking its potential. In its own paradoxical way, to acknowledge the seams in the cinematic device is to open a path to the story's truth. The fakest it looks, the more The Matrix registers as an admittance of its limitations, and the more the viewer is seduced into accepting the heart and soul of the picture.

Making matters run smoother, we can also find hints of retroactive nostalgia and an undercurrent of dream logic, especially noticeable in the early passages. A somnambulistic wandering, one feels that the movie eagerly anticipates the moment Neo wakes up.

Know thyself. I wanna tell you a little secret: Being the One is just like being in love. No one needs to tell you you are in love, you just know it, through and through.

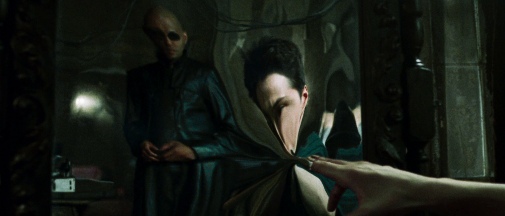

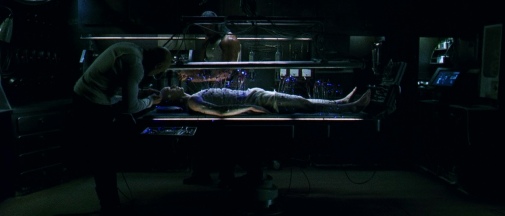

His awakening is staged by the Wachowskis like rebirth from a technological amniotic sack, all goo and mechanic unplugging. With every tube extracted, the smooth, newborn-looking body is left littered with holes that must heal and become permanent ports into the virtual cosmos of limitless possibility. Neo needs to be therapeutically prepared for life in this new physiognomy that was there all along, waiting for the moment he could experience it fully. But before that instant, the normative body had to be somewhat destroyed. Or, at least, the idea of its inflexibility needed to be bent out of shape. Thus, Neo's path goes through the looking glass, a mirror expanding and consuming him whole, boa constrictor-like. It's another Alice reference and a meditation on mirrors themselves.

Those objects confront and differ from one's self-image. At their worst, what you see when gazing upon their surface feels like a lie. Believing in your truth with enough conviction breaks through the mind-numbing anesthetics of the Matrix's societal status quo, and through the mirror, too. It's as if mutability were Humanity's essence and greatest weapon. Our ability to adapt and change, to look past the reflection. Our willingness to find the truth even when outside forces try to oppress us according to an order that's antithetical to the human condition. And since the Wachowskis are romantics, the conviction to find love is also present.

Love shall be the key to Neo and Trinity's saga, from this first part to Resurrections. And love can only be found once you find yourself and become who you are, not what the world expects you to be.

I'm going to show them a world without you. A world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries. A world where anything is possible. Where we go from there is a choice I leave to you.

In The Matrix sequels, Neo's Chosen One status would be questioned and problematized, with the future of Humanity diverging from victory against the machines into something more akin to symbiosis. Even so, regarding the first movie alone, we find that the enemy's greatest weapon – the illusion of normalcy – is the most inhuman structure of them all, a force that crushes beings much more multifaceted and mysterious than whatever their mechanic overlords might suppose. "Reality" itself is a construct, a cis-tyranny bound to be dismantled by the Wachowskis' trans-coded Jesus, who dies and is reborn into his true self when breaking through the simulation. They will show us a utopian tomorrow, a world without boundaries and strict binaries. Heteronormative and cisgender hegemony will be left behind, broken and obsolete. At least, that's the dream.

On the Trans Day of Visibility, I raise a glass to that dream and invite you all to do the same. Cheers!

Reader Comments (2)

Exceptionally well researched and thorough. Always interesting to read your takes and this one is especially eye-opening!

Abe -- Thank you for those kind words. I'm glad you liked reading this.