Sherlock Jr. @100: For the love of Cinema

Thursday, April 18, 2024 at 7:00PM

Thursday, April 18, 2024 at 7:00PM

This week, one of the best comedies ever made and a silent film masterpiece celebrates its centennial. It's none other than Sherlock Jr., Buster Keaton's 45-minute miracle of stunt work and cinematic considerations about cinema as materialized dream and broken escapism. A meta-movie for the ages, I consider it the old Stone Face's crowning achievement. Sure, The General is much more complex and Steamboat Bill, Jr. trumps it in sheer iconography. As for technical innovation, something like The Play House is probably Keaton's peak. However, there's something special about the 1924 lark, a simplicity that bolsters perfection, an ingenuity that rekindles my love for cinema whenever I set my eyes on it…

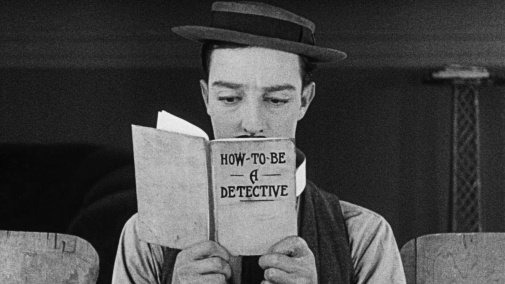

Sherlock Jr. is the story of the humble Projectionist, a feckless young man who dreams of being a detective while working in the local cinema. As befits a movie built on archetypes, he gets no name, and neither do his fellow players. There's a Girl he's in love with and a rival for her affections, the so-called Sheik, who enters the film by purloining a watch from the Girl's Father. With the cash he gains from pawning it, the Sheik courts his amorous target, while the Projectionist is sabotaged every step of the way, whether by the Sheik or Lady Luck. It's a simple tale where only Keaton's leading man is allowed some complexity in reaction and perceivable personality.

It's also just table-setting for the movie's raison d'être. As he'd describe in later years, Buster Keaton wanted to make Sherlock Jr. based on one single image, the point of separation between acts right in the middle of its structure. It's the moment when, having fallen asleep on the job thanks to some bad detective picture, the Projectionist's unconscious mind abandons his slumbering body and wanders into the projected image. Suddenly, he's in the unreality of the silver screen, living as his ideal self through an adventure that could be mistaken for a celluloid spin on Dorothy's trip into Oz if Judy Garland was a sad-faced stuntwoman with a deathwish. By the end of this chaotic dream, the Projectionist is a hero, and upon waking up, he gets the girl in a mimicry of the lovers on screen.

Was the trespass from the mundane world into cinema's land of imagination the film's genesis, or was Keaton tweaking with the production history after the fact? Hard to say. Supposedly, a post-trial Roscoe "Fattie" Arbuckle was meant to be the project's co-director, but reports also vary on his involvement. Indeed, Doris Deane – Arbuckle's second wife – even claimed he was the mastermind behind Sherlock Jr.'s most memorable bits. On the contrary, Keaton claimed his former colleague was eventually forced out of the project and made to direct The Red Mill, which was only completed three years later.

That's just one of multiple anecdotes and controversial curiosities surrounding the classic. It's also believed that it was during the shoot that Keaton suffered one of his most debilitating accidents, breaking his neck. But for all that these behind-the-scenes details might color one's appreciation of Sherlock Jr., its magnificence lives beyond them. There's no arguing against the marvel on screen. Even before the Projectionist escapes into a dream, Keaton's skill is on full display. Notice the rhythmic precision that goes beyond mere cutting, how human behavior is staged into a ballet of funny gags.

The characters' movements are choreographed according to a silent metronome, and every reaction rings with comedic intent. The failed courtship in the first half is as carefully engineered as Keaton's wildest stunts in the second part of the narrative when Sherlock Jr. turns into a legendary chase. There's finesse in a banana peel pratfall early on and a crazed ferocity in the athleticism of the star's most daredevil feats near the end – though neither violates the impassivity of his facial expressions. The dream logic is another point of interest, for it transforms the picture's pop culture satire into something more enchanting.

Much of Sherlock Jr.'s core ideas depend on an acknowledgment of media artifice. Life outside the movies is a quotidian full of disappointments, with what happens on screen being ruled by much freer rules than what defines human existence. In other words, movies are magic and nonsense wrapped into one, a response to our need for respite and escape. That's why the oneiric and the cinematic can combine so well, creating an impression of the Projectionist's imagination unbound and a commentary on Hollywood tropes circa 1924. It's both showcasing the silliness of the device and proving why it works.

On a formal level, geographical inconsistencies abound in the characters' traverse through spaces, and the impossible often occurs. A mirror defined by compositional convention is shown to be non-existent when our hero walks through it and commonplace trunks have disproportionate depths, enough to fit a whole Buster Keaton. Another visual motif is the proliferation of frames within frames as if the dreamed movie is itself compartmentalizing and compartmentalized by smaller tableaux. Tricks of editing affect the Projectionist in his dream, the mechanisms that make cinema work, calling attention to their falsity and boundlessness.

Consider another tension woven into the fabric of Keaton's movie. Years before sound technology would drag the American film industry back to the studio, the outdoor photography conveys a sense of material reality to his most lunatic stunts. Even though Sherlock Jr's misadventures are oneiric in nature, we sense the performer's danger and feel all the more thrilled because of it. It's intoxicating, like getting drunk on a shot of distilled adrenaline. Film must be fake to be fun, but the material foundations of it need not be contrary to the audience's entertainment – a touch of real enhances the experience just like Keaton's unsmiling visage makes his clownery extra hilarious.

In contrast, bringing your dreams into reality is less wonderful. They don't belong there. They don't work beyond the frame of movies. That's partly why, though the Projectionist gets everything he wanted in the end, the look on his face isn't uncomplicated bliss. Moreover, making sense of what's happening, he takes his cues from the screen heroes for a final romantic gesture. Sherlock Jr. isn't just a dream story but a film looking at itself and pointing out its absurdities. In the process, it invites us to laugh and marvel at it all. It's a burst of creative energy so exhilarating you may not realize it's laden with heady concepts. Combining irony with a sincere love for the big screen, Sherlock Jr. is one of those films that will remind one why they fell for cinema in the first place.

Sherlock Jr. is streaming on Apple TV+, Classix, Indie Flix, Flix Fling, Kanopy, Plex, Pop Flix, and Public Domain Movies. You can also rent and buy it on most of the major platforms.

Reader Comments (3)

I do love this film as I could see why some prefer Keaton over Chaplin as he is a great director and does a lot of attention to detail when it comes to stunt work. I'm more impressed in what he, Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Jackie Chan do with their stunts than that aging midget who likes to jump on couches does.

I love this site for things like this - recognizing and celebrating a 100-year-old classic!

You serve an underserved audience, TFE

Mike in Canada -- Thank you so much for your kind words. Glad you appreciate the work.