Michael checking in.

Michael checking in.

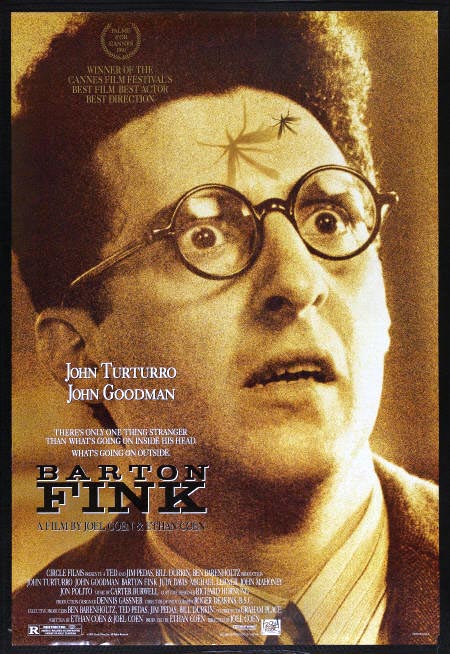

My first introduction to the brothers Coen was viewing Fargo on VHS at age 16 and nothing since that memorable night has been able to dislodge it as my favorite of their films, although a college-aged love affair with Milller’s Crossing came closest. But even as Marge and Jerry have remained secure on their pedestal, I have returned to none of the Coen brothers films more often than 1991's Barton Fink. Not even the compulsively rewatchable Big Lebowski has kept me coming back more consistently.

So as Barton Fink turns twenty years old (tomorrow), I wonder what it is about the Coen's Cannes-winning, surreal, showbiz fever dream keeps me so fascinated?

I certainly don’t return compulsively to solve mysteries of the story, that’s for sure. The Coens may plot their stories with a Swiss watch precision that suggests all the answers are there if you look hard enough, but the ambiguity the brothers place in their movies is deliberate, and not meant to be puzzled out to a solution. The Coens often feature unanswerable questions prominently in their stories. What did, after all, happen in the hotel room in No Country for Old Men where Javier Bardem seemed to vanish into thin air? What motivated Gabriel Byrne’s character in Miller’s Crossing? What was the meaning of the prologue in Serious Man? Or the epilogue in True Grit?

Written, the brothers say, as they struggled to untangle the plot of Miller’s Crossing, Barton Fink is the story of a lefty playwright in the early forties who has one hit on Broadway and promptly goes to Hollywood to sell out only to find himself facing an epic case of writer’s block. Taken simply Fink would earn a place in the canon as one of the most wicked Hollywood satires ever put to film. But, as most everybody knows, Barton Fink cannot be taken simply. At the three quarters mark Fink takes one of the all time most jawdropping plunges into surreality, and audiences to this day are still trying to make sense of it all, from the contents of Barton's mystery box to the beach painting on his wall.

Barton Fink theories are numerous and fun and I could fill a book debating them all. The most obvious of course is that Barton is in Hell. The clues for supporting this range from obvious like the omnipresent heat to subtle like the repetition of the number six in the elevator. Once you start looking for clues you can find them everywhere. On my most recent viewing I just picked up on the suggestive names of wrestling pictures - “Hell Ten Feet Squared” and “Devil on a Canvas”.

Do you see what happens Larry?"

Then there are the theories about Barton Fink being about the rise of fascism represented by Charlie Meadows with Barton as the intellectual too feeble to notice or stop it. The most glaring red flag in the movie is Goodman’s pronouncement of “Heil Hitler” before he kills one of the detectives which is certainly no accident. But if Goodman represents evil why does he kill the detectives who, with their noticeably German and Italian names, clearly represent the Axis powers? I for one have always read his delivery of "Heil Hitler" as sarcasm before killing the anti-semitic detective, but what does it matter? We should take a cue from the character in Serious Man and “embrace the mystery” or it will lead you in circles like walking an MC Escher staircase.

Once you give up trying to solve what needn’t be solved you can settle in and get the full Barton Fink experience. The film is genuinely hilarious and every word out of Michael Lerner’s mouth as the vulgar studio boss is solid gold. Fink also contains what I consider to be John Goodman’s all time best performance (I know that is saying a lot). Lerner got the nominatio but Goodman would have been my choice to win the trophy that year. And speaking of Oscars, when everyone was bemoaning that Roger Deakins lost an absurd ninth time this year for the cinematography of True Grit they might just as well added that it should have been his tenth, because he was royally screwed out of nod for Fink.

Or maybe you can just forget all that and just groove on all the endless supply of haunting, weird touches the Coens place in every scene of Fink, my favorite being the endlessly humming bell that Barton rings to summon Buscemi’s Chet from the Underworld. There is also the strange dying bird at the film’s end, which is supposedly just a moment of happenstance caught on film, or the bizarre fact that it is clearly John Turtorro’s voice as one of the actors in the play that opens the film. What are we to make of that?

Or maybe you can just forget all that and just groove on all the endless supply of haunting, weird touches the Coens place in every scene of Fink, my favorite being the endlessly humming bell that Barton rings to summon Buscemi’s Chet from the Underworld. There is also the strange dying bird at the film’s end, which is supposedly just a moment of happenstance caught on film, or the bizarre fact that it is clearly John Turtorro’s voice as one of the actors in the play that opens the film. What are we to make of that?

Slate magazine recently did a retrospective of the Coen’s body of work complete with a poll ranking the films. I was chagrinned but not surprised to see Barton Fink languishing in the lower half of the poll. This is always the way with the connoisseur’s choice. Barton Fink is the Coen’s in their purest most undiluted form, and film’s like that never win the popularity contest. They do however win the test of time as they draw audiences back over and over again to explore their depths.

Wednesday, July 22, 2020 at 1:34PM

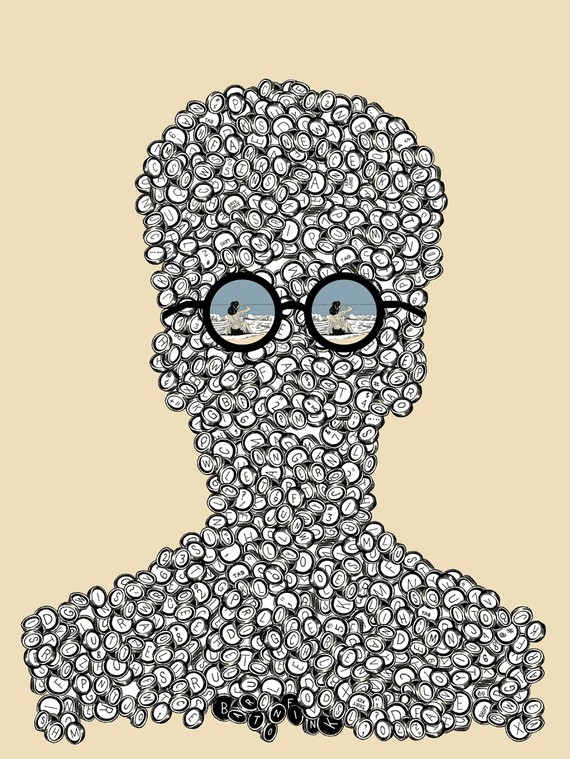

Wednesday, July 22, 2020 at 1:34PM  What is the wallpaper of the Common Man? It’s a strange question, but Barton Fink is a strange movie. The titular writer (John Turturro) is a man consumed by passion for the clichéd unsung hero, though he would never go so far as to actually ask a Common Man what he thinks. His obsession is really with the idea of the Common Man, abstract and waiting to be tossed onstage or slapped onto the blank canvas of a movie screen.

What is the wallpaper of the Common Man? It’s a strange question, but Barton Fink is a strange movie. The titular writer (John Turturro) is a man consumed by passion for the clichéd unsung hero, though he would never go so far as to actually ask a Common Man what he thinks. His obsession is really with the idea of the Common Man, abstract and waiting to be tossed onstage or slapped onto the blank canvas of a movie screen.