Craig from Dark Eye Socket here with Take Three. Today: Boris Karloff

Take One: The Mummy (1931)

Always the consummate character actor, Karloff gave us the most splendidly memorable characters. Famously one of the world’s biggest and best horror icons (along with Lugosi, Chaney Jr., Price and Lee, the frightful five), he played his beasts, ghouls and undead wanderers in exemplary fashion. Take his Imhotep/Ardath Bey, the titular bandaged one in director-cinematographer Karl Freund’s 1931 classic The Mummy. Ten years after being awakened by a group of foolhardy archaeologists Imhotep intends to revive his ancient Egyptian love Princess Ankh-es-en-amon with the help of reluctant modern-day babe Zita Johann.

Museum-based murder and an ancient parchment (the Scroll of Thoth!) cause all the the mummified mysticism. Karloff even has his own Pool of Fate (essentially a steamy bath/psychic porthole), into which he can see anyone and anything, anywhere; and via which he causes the remote heart failure of any old duffer who happens to get in his way. It’s all in the seeing here, all about the Mummy’s eyes. Karloff is given three intermittent extreme close-ups where he glowers into the camera, hypnotising us with his devilish ways. His eye sockets appear as black, lifeless voids into which his bright white pupils emerge through a trick of the light (director Freund was also a celebrated cinematographer). Imhotep is unnervingly memorable.

Take Two: Black Sabbath (1963)

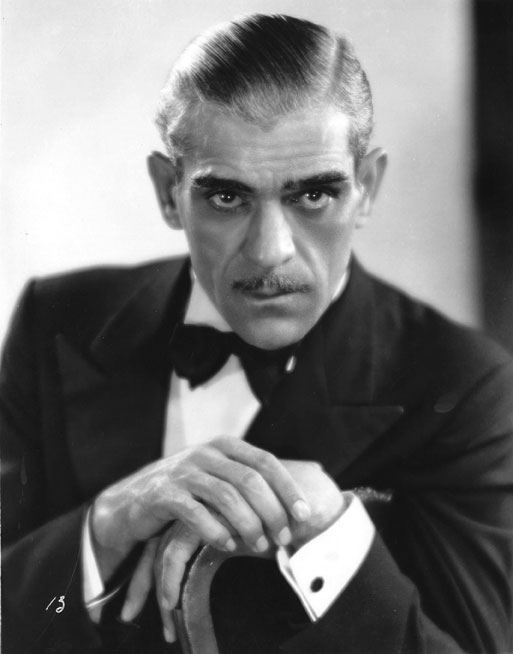

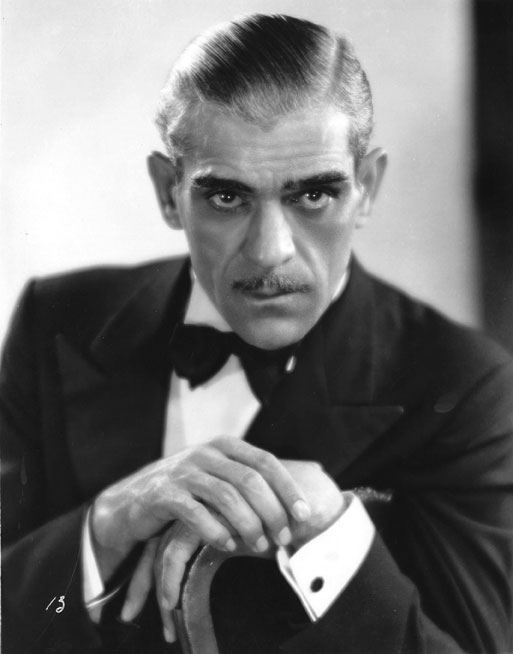

Black Sabbath (AKA I Tre volti della paura or The Three Faces of Fear) was one of Karloff’s key later roles – and a horror-fan favourite. This second segment, The Wurdalak, of Mario Bava's 1963 horror triptych* sees a Russian nobleman seeking shelter in a cottage run by a family awaiting the return of their father Gorca (Karloff). The family fears he may be the titular vampiric creature come back to damn them all to hell or condemn them to a life of blood-lusting misery, whichever comes first. With ashen face and oversized follicle accompaniments (his curly wig, moustache and eyebrows deserve their own end-titles credit), Karloff stands out. And I mean that literally, as well as performance-wise; the star is seen standing outside peering in on the action much of the time. Karloff is also lit by horror-versed cinematographer Ubaldo Terzano in a different, far more singular way than the other actors are. The giddy weight of his presence perhaps aroused nostalgic creativity in Bava. Karloff, so familiar from classic creature features, appears like an ornery flickering wraith from a beloved bygone era.

Bava, like Freund, makes effectively chilling use of Karloff’s penetrating eyes. He knew that all it took to match Boris’ unique ability to transfix an audience with great, creepy eye-work was the requisite camerawork to capture it.

*Karloff’s performance is also notable for the fact that he appears as himself in the interludes, where he introduces the scary stories to follow.

Take Three: Frankenstein (1931)

and Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

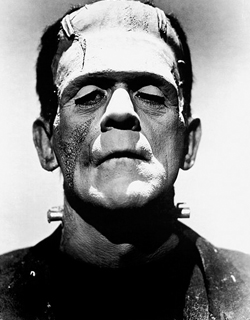

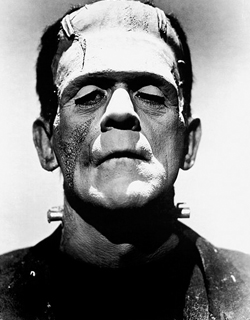

In James Whale’s germinal horror film Frankenstein Karloff is introduced to us simply as ‘?’. He’s a mystery, an enigma: a monster! He’s a confused soul, a man made out of bits of other men, bad men. Karloff comes alive halfway through this epoch-defining original mutant anti-hero movie. He’s first shown via a shot of his hands (as he similarly was in The Mummy and, indeed, in Bride of Frankenstein – it seems to be a recurring trope); he twitches his fingers then rises to meet a world of fear and epic paranoia. It was simply a way of being and walking: arms aloft, that angular, towering body – matched with the bolt-necked, flat-topped patchwork head, fronted by that memorably permanent crestfallen expression. Karloff delivers a beautiful performance, inventively clumsy and expertly physical.

In the first film he was quicker, more erratic. In Bride – with nearly five years' worth of living with the Frankenstein legend surrounding him – Karloff appeared more at home, looser and familiar with the moaning and groaning through fields and ruins, but no less energetically committed. It’s like he dusted off the monster’s clothes four minutes, not four years, after first wearing them so well. As a result, one of Karloff’s monstrous turns can’t truly be judged higher than the other. They’re a complementary couplet, both eminently watchable and always fascinating. But Bride reveals more about the man within the monster. It's evident in the three instances where he sheds a tear. You see that those tears are born of loneliness: he craves companionship. You can feel nothing but vicarious sorrow when the third of his tears works its way down his scarred, sunken cheek.

We belong dead.

...the monster forlornly admits in a last, generous close-up from James Whale. Boris Karloff made this famous monster indelibly his own.

Three more films for the taking: The Black Cat (1934), The Body Snatcher (1945), The Sorcerers (1967)

Thursday, October 26, 2023 at 9:00PM

Thursday, October 26, 2023 at 9:00PM