Cold Eyes and Weary Bodies in "Hud"

Thursday, May 30, 2013 at 7:55AM

Thursday, May 30, 2013 at 7:55AM For this week's Hit Me With Your Best Shot we're celebrating Hud on it's 50th anniversary

Though I readily concede that its my own prejudices as a Yank and a cityboy that get in the way, I rarely associate nuanced feeling with the western genre or artful dialogue with a Texas twang. So Hud (1963) plays like a miracle to me, a major one. This adaptation of Larry McMurty's novel (he would later write screenplays including Brokeback Mountain, which plays like a distant cousin to this 1960s masterpiece) never feels anything less than authentic in its Southwestern reality and yet its pure poetry. Consider this callous but perfectly sculpted line of dialogue from Hud (Paul Newman in arguably his finest hour) to his nephew Lon (Brandon deWilde) who is worrying about Homer's (Melvyn Douglas), the paterfamilia's, waning health.

Happens to everybody - horses, dogs, men; nobody gets out of life alive

But I'm not really here to talk about the rough beauty of the dialogue in Hud -- though it's never far from my mind -- but the language of the eyes and the body delivering it. And, I rush to add, the award-winning cinematography and composition which package the unimproveable ensemble up so potently. Look at the shadows and the way Newman, bathed in light, become a handsome devil (essentially the truth of his character) his famous blue eyes less like inviting pools of water than icy death.

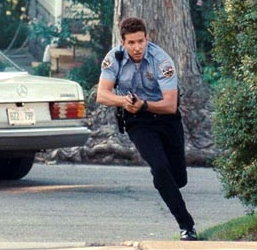

But we'll return to close ups shortly. Much of Hud is shot in medium and long shot and everywhere you look, limbs are dangling and swaying and whole bodies are sneaking brief moments of rest, perched on porches, settling into chairs, or suggestively refusing to leave their beds. Melvyn Douglas and Patricia Neal, as the family's housekeeper Alma, both won deserved Oscars for their inspired work, and they beautifully capture not just the details of their characters but the physicality of people who've worked their bodies every day of their lives whether cattle rustling or scrubbing dishes. The younger characters Lon and Hud, are less exhausted, though there's still a kind of future arthritic effort to their jerky performative posing.

runner up for best shot. Hud is a big deal

runner up for best shot. Hud is a big deal

Lonnie: I'll go with you Hud.

Hud: What big deal you got lined up, sport - a snowcone or something?"

Take one of the best scenes in Hud on the porch of the family house while the characters eat peach ice cream and enter and exit the frame without the camera following them (though Hud is quite cinematic, this particular scene is blocked like a play). Lon and his granddad have a fascinatingly evasive exchange about Hud's dead brother (Lon's dad) and why Homer dislikes his only living son "He knows. You don't need to." Douglas delivers each line with evasive though never rude gruffness, his cards held tight to his chest. When Hud enters the scene and announces a run into town, Lon shifts his attention to the uncle he idolizes but doesn't understand. There's this exquisitely telling funny shot of him mirroring Hud's pose -- while Hud mocks him but invites him to tag along anyway. How brilliant that it takes a second to even figure whose shadow is thrown onto the wall.

The withholding father and his ungrateful child finally have it out in the film's centerpiece, a truly seismic emotional clash (the first hour being foreshadowing tremor and the second cruel aftershock) which Hud believes is entirely about his dead brother - the son Homer adored - which Homer denies. The righteous father tears into Hud as a man without principle, without empathy for his fellow man, without care for the world around him. Hud listens with silent hostility (he knows it's true) in one of the most gloriously lit and perfectly acted close-ups in all of cinema - my choice for best shot - as water from the well drips down his angry face. That's the closest he'll ever get to human tears in the film though Hud may have once shed them for the mutual loss that ripped them apart 15 years earlier. His cool eyes shift with a cruel smile as the room falls silent until he finds an unexpected nonsequitor to hurt both of them, and shoves the dagger in.

his mamma loved him but she died

his mamma loved him but she died

My mamma loved me but she died."

This scene never fails to tear me up inside and deeply impress me for myriad reasons but precisely for the writing, the lighting, blocking and precise direction by Martin Ritt (Norma Rae, Cross Creek, Sounder) and the peak moment of Newman's indelible cold, cruel star turn.

Frank Langella the actor recently dissed Paul Newman's acting reputation in his memoir "Dropped Names: Famous Men & Women as I Knew Them" saying that while he was a great movie star he was not a great actor. His reasoning was that Newman lacked the one thing that Langella figures all great actors have - danger. I can only surmise that Langella never saw Hud. For Paul Newman was both a great movie star and a great actor and Hud is the proof of it. Even if his career had ended there he'd still be legendary. There's enough danger in his hostile beauty in Hud to scar everyone in his orbit.

Hud: I don't usually get rough on my women. Generally don't have to.

Alma: You're rough on everyone.

Other "Best Shot" Must-Reads on Hud For its 50th Anniversary

- We Recycle Movies compares the rape scenes of The Fountainhead and Hud, one glamourized the other decidedly not

- The Film's the Thing finds that Hud is not at all the motion picture he assumed it to be

- Film Actually see it as primarily a writers film

- Antagony & Ecstasy on the pulverizing and "amazing as hell" movie

- Entertainment Junkie on Neal's brilliant balancing act and Newman's indelibly solitary antihero

- A Fistful of Film James Wong Howe was in love with Paul Newman!