Amir Soltani is covering the Berlin International Film Festival for The Film Experience this year, our first time at Berlinale!. For his first dispatch, he’s reviewed Tunisia’s Hedi

Amir Soltani is covering the Berlin International Film Festival for The Film Experience this year, our first time at Berlinale!. For his first dispatch, he’s reviewed Tunisia’s Hedi

Although Hedi (Inhebbek Hedi) is Mohamed Ben Attia’s first feature film, it comes with the pedigree of being co-produced by the Dardenne brothers, and it’s not difficult to see why they were drawn to this story. Hedi (Majd Mastoura), a 25-year-old, Tunisian car salesman, would fit neatly into the gritty, realist universes of the brothers’ working class protagonists. A slow-burn study of an unhappy young man on the verge of getting married, Hedi builds up to an intensely emotional, rewarding finale that is once personal and political.

Under the overbearing, towering influence of the family’s matriarch, Hedi is the second of two sons whose father has passed away. Whereas the elder son has moved to France and lives with his French wife and daughter – much to his mother’s chagrin – Hedi remains in Tunisia, working a job he neither enjoys, nor seems to flourish in. He is engaged to be married to Khedija (Omnia Be Ghali), a modest, traditional girl whose dreams about married life and her insistence on celibacy are equally endearing and claustrophobic to Hedi. Yet, what seems like a monotonous, unsatisfying existence is set ablaze when Hedi meets Rim (Rym Ben Messaoud), a travelling dancer at a local hotel, mere days before his planned wedding.

Mastoura plays Hedi with stoic detachment, an approach to the character that allows the audience to project onto him a whole range of emotions that Hedi cannot express. As the film progresses, and different facets of the oppressive environment and communal culture in which he lives are revealed, the character, and Mastoura’s performance, become increasingly more identifiable. The movie isn’t as generous to its secondary characters, rarely affording any of them the chance to establish themselves without relation to Hedi, but the uniformly strong performances of the cast, particularly the warm and enchanting Ben Messaoud’s create fully realized characters.

Ben Attia’s sharply constructed film uses visual markers to put us in Hedi’s headspace, with subtle shifts in the rhythms of the film’s handheld cinematography and brief glimpses into Hedi’s hand-drawn comic strips. His rooted but trembling ties to anachronistic traditionalism become symbolic of the country at large. This is a piercing character study, a deeply felt film about the complications and confusions of youth that, through its focused lens, rewards the audience with a story about the broader implications of liberation from tradition, on a personal level and, allegorically, for the North African country at large.

Friday, July 12, 2019 at 8:09PM

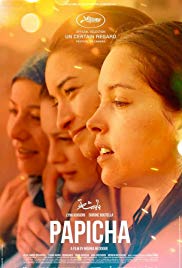

Friday, July 12, 2019 at 8:09PM  We were waiting to see which European country would be first to announce before publishing our famous Oscar submission pages. But an African country surprised us by being first up to bat. Word is in that Algeria will submit Papicha as their Oscar entry this year.

We were waiting to see which European country would be first to announce before publishing our famous Oscar submission pages. But an African country surprised us by being first up to bat. Word is in that Algeria will submit Papicha as their Oscar entry this year.