Robert here, with my series Distant Relatives, where we look at two films, (one classic, one modern) related through a common theme and ask what their similarities and differences can tell us about the evolution of cinema. This week there are definitely SPOILERS AHEAD, not necessarily specifics but revelations in terms of happy ending or sad ending. Be forewarned.

Two men looking for the American Dream

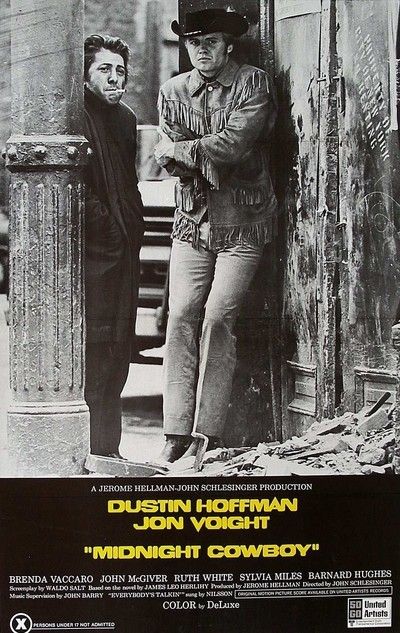

In the 1960's Easy Rider, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Midnight Cowboy and other films followed an emerging theme, two brethren on a quest for success, triumph, togetherness, the American Dream. It may seem odd to consider The Fighter a descendant of this type of film. Indeed The Fighter (2010) and Midnight Cowboy (1969) come to drastically different conclusions about how attainable the dream is, but their journies to that concusion are consipuciously similar, especially in terms of the relationship between the two men at the center of the stories.

In Midnight Cowboy, Joe Buck (Jon Voight) has dreams of making it big in the male prostitution business, but can't seem to get out of small time transactions. "Ratso" Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), the untrustworthy but sympathetic loser who eventually takes him under his wing, has no hope in life without Joe. When Joe makes Rizzo his manager of sorts it's a move that he needs and yet one that keeps him teetering on the edge of success and failure. Eventually the men will become brothers in their quest for a better life. So it is with real life Mickie Ward (Mark Wahlberg), the underachieving boxer who needs his actual brother Dickie (Christian Bale), a drug addict and perpetual screw-up, but the only man who can lead him to a world championship.

The Adonis and the Scofflaw

The two man story structure isn't anything new, nor was it anything new when our earlier film was made in the 1960's. In fact, in the world of comedy, the straight man/comic relief duo has always been standard. And it's that structure that both of our stories share in common. Not to suggest Ratso or Dickie are "comic relief." They're definitely the more animated character who stands in direct contrast to their straight man. This is what makes Midnight Cowboy the more significant cousin to The Fighter. Butch and Sundance don't have this dramatic a dynamic, nor do Billy and Wyatt.

While The Fighter asks us to make comparisons between Dickie's past failure and Micky's impending failure that Midnight Cowboy does not, both present a picture of men on different sides of their hopes and dreams, one beyond hope, and one filled with it. They are a contrast of sickness and health.

A man's got to make a living

Consider also the similarities between the jobs of Joe Buck and Micky Ward. I don't mean to suggest that the legitimate pursuit of boxing is equal to prostitution, however both present opportunities for the film to comment on the projection of the protagonist's success, one opponent/clinet at a time. Something between luck and talent lead to whether the next opponent/client will be an improvement over the last, a step in the right direction. So it is with the American Dream, half luck, half talent. But in these cases, all the more apparent when noticed one job at a time.

Inevitably Midnight Cowboy ends by declaring the death of the dream, and finishes off with an actual death to symbolize this. For The Fighter the dream is achieved, renewed even through the symbolic renewal of a character. Is the fact that the modern film ends happily a sign that audiences reject the suggestion that the dream is dead? Not necessarily. The truth is far more complex than that. Plenty of films with harshly realistic endings these days find success on their own level. Suggestions about the declining taste or tolerance of the modern moviegoer need not be marked against a film as lauded as The Fighter. What is telling about the film is, considering just how many inspirational sports films, even boxing films, there are, filmmakers wanted to tell this story. It is perhaps because it presents something new to the feel-good genre: the idea of opposites, but brothers, playing off each other in their quest for something great.

Saturday, June 17, 2023 at 12:00PM

Saturday, June 17, 2023 at 12:00PM

Doc Corner,

Doc Corner,  John Ford,

John Ford,  Jon Voight,

Jon Voight,  Midnight Cowboy,

Midnight Cowboy,  Review,

Review,  documentaries,

documentaries,  westerns

westerns