Best Supporting Actress in the 80s: An Alternative Oscar History

Friday, November 15, 2024 at 10:00AM

Friday, November 15, 2024 at 10:00AM  Out of Oscar's Best Supporting Actress winners from the 80s, Anjelica Huston is the only one who repeats the feat in my ballot. But not for PRIZZI'S HONOR!

Out of Oscar's Best Supporting Actress winners from the 80s, Anjelica Huston is the only one who repeats the feat in my ballot. But not for PRIZZI'S HONOR!

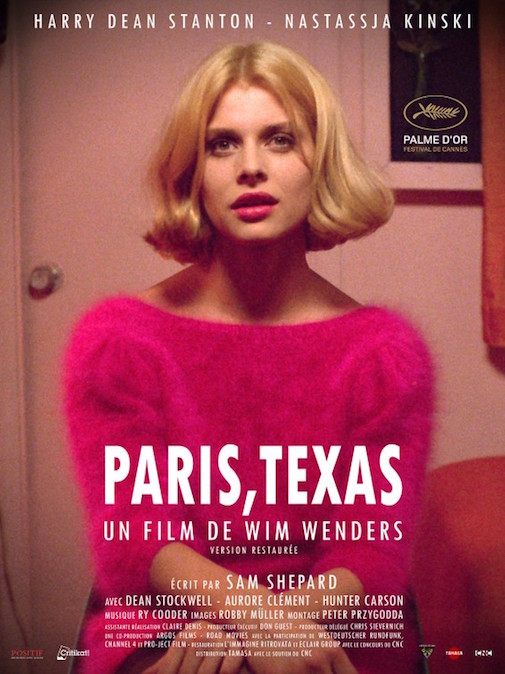

Since the Best Actress post did so well, let's tackle another category in my Alternate Oscar history. We're still keeping with the thespians and the divas, because those are always the most beloved races here at The Film Experience. Once again, I followed Oscar eligibility rules when building these ballots, but also included honorable mentions, ineligible standouts, and some enticing prospects for some future movie-watching adventures. Any and all recommendations are welcome, of course, and you're welcome to tear these lineups to shreds – as if you needed an invitation. From 1980 to 1989, from actresses playing actresses to screen sirens for the videotape age, here are my Best Supporting Actress picks for our "Totally Awesome 80s" month…